Abstract

Background: Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths. This study aimed to determine the survival of patients with HCC at our treatment facility.

Methods: We retrospectively studied 278 patients with HCC who were seen between 2007 and 2013. Of these patients, 84.4% had evidence of prior infection with hepatitis C, while 7.8% had markers of hepatitis B infection.

Results: Median survival was 24.6 months for transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), 61 months for ablative therapies, and 31.5 months for those undergoing surgical resection. Increasing tumor size, multifocality, advanced Barcelona clinic liver cancer (BCLC) stage, and poor liver function (Child-Pugh class B-C) were significantly associated with worse prognosis; pvalues were 0.002, 0.009, <0.001, and <0.001, respectively.

Conclusion: Most patients in our series presented with advanced liver disease, with multifocal tumors and were candidates for palliative treatment only. Public education to minimize hepatitis B and C transmission, screening programs to detect disease at an earlier stage, and the development of specialist liver units and liver transplant programs can bring a change in HCC survival in developing countries.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is common, and although it affects different regions of the world disproportionately, worldwide it remains the seventh most frequent cancer and the third most common cause of cancer-related deaths, causing approximately 600,000 deaths annually 1,2,3. Its incidence has almost doubled in Western countries in the past 20 years, primarily due to an increase in alcohol and hepatitis C-related liver cirrhosis4,5. However, more than 80% of cases occur in the developing world and in areas with a high prevalence of hepatitis B and C, such as China, southeast Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa, where its incidence is as high as >20/100,0001,3,6. With universal screening of high risk populations, early detection and treatment, the five-year survival rate of those with HCC can be as high as 70%, after ablation, resection or liver transplant. Patients in whom HCC is detected by surveillance have a three-year survival rate of 50.8%, compared to 28.2% in those not on a surveillance program. This difference in survival is largely due to detection at an earlier stage, with better resultant treatment options7.

In intermediate stage HCC, the two-year survival rate is 49%, while median survival is 16 months; in advanced stage HCC, the one-year survival is 11% with a median survival of 3-4 months8,9.

Methods

Evaluations

We retrospectively analyzed demographic, etiological, clinical and therapeutic variables of 278 patients with HCC, treated at the tertiary care Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Center, in Lahore, Pakistan from May 2007 til December 2013. They were treated after obtaining exemption for approval from the Institutional Review Board. The study was retrospective, in accordance with the principles of Helsinski’s declaration. Data was collected using the computerized hospital database, and from evaluating the clinical and multidisciplinary team meeting notes, pathology and radiology reports, and information obtained from patients and their families by telephonic surveys.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the survival of patients with HCC arising as a result of a variety of etiologies and to attempt to correlate survival with liver function, tumor focality, size, and stage, as well as with serum alpha-fetoprotein level and treatment regimen.

In the majority of our patients, the initial liver lesion was detected on ultrasonography, and then further evaluated by multiphase computed tomography (CT) scan. The diagnosis was based, for the most part, on characteristic findings on imaging, in appropriately-sized lesions in a typical clinical setting, following EASL/AASLD guidelines. Lesions that showed multiphase magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were further evaluated for atypical vascular enhancement pattern on multiphase CT scan. If on MRI the tumor showed characteristic radiological features of HCC, then the diagnosis of HCC was considered to be confirmed, assuming again an appropriate clinical setting. If the lesion remained atypical on MRI, image-guided liver biopsy was performed, and the diagnosis was established if it showed the characteristic histological features of HCC.

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. Hepatitis C virus infection, detected either by HCV antibodies by third generation ELISA or by HCV RNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), was the most common risk factor for chronic liver disease. HCV infection was present, either alone or in combination with diabetes mellitus, in 83% (231/278) of the study population. Hepatitis B virus infection (detected by the presence of hepatitis B surface antigen or by HBV DNA by PCR), either alone or in combination with diabetes mellitus, was the second most common risk factor, and was present in 7.8% (22/278) of the patients; five of these patients also had hepatitis C. Alcohol consumption, as the only risk factor, was present in only two patients, but was present in another eight patients in combination with diabetes and accounted for 3.6% (10/278) of the study population.

| Variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 60 (9.2) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male/female | 192/86 | 69/31 |

| Cirrhosis | ||

| Child-Pugh Class A | 234 | 84 |

| Child-Pugh Class B | 32 | 11.5 |

| Child-Pugh Class C | 12 | 4.3 |

| Risk factors | ||

| Hepatitis C | 150 | 54 |

| Hepatitis C+DM | 81 | 29 |

| Hepatitis B±DM | 17 | 6 |

| Hepatitis B+C±DM | 5 | 1.8 |

| DM± alcohol | 10 | 3.6 |

| No risk factors | 15 | 5.4 |

| BCLC† stage | ||

| BCLC stage A | 95 | 34.2 |

| BCLC stage B | 144 | 51.8 |

| BCLC stage C | 27 | 9.7 |

| BCLC stage D | 12 | 4.3 |

| No of HCC nodules | ||

| Unifocal | 140 | 50.4 |

| Multifocal | 138 | 49.6 |

| Diameter of largest HCC nodule | ||

| ≤ 3 cm | 45 | 16.2 |

| >3-5 cm | 119 | 42.8 |

| >5cm | 114 | 41 |

| AFP | ||

| <300 IU/ml | 178 | 64 |

| ≥300 IU/ml | 94 | 33.8 |

| Missing | 6 | 2.2 |

| Treatment | ||

| TACE‡ | 181 | 65.1 |

| TACE with other treatments (Resection, RFA, PEI, Sorafenib) | 23 | 8.3 |

| Ablation (RFA, PEI) | 12 | 4.3 |

| Surgical resection | 6 | 2.2 |

| Sorafenib | 14 | 5 |

| Supportive care only | 42 | 15.1 |

The number of patients with unifocal (50.4%; 140/278) and multifocal (49.6%; 138/278) tumors were very similar. However, only 16.2% of patients had tumors <3 cm in size, while 83.8% had tumors ≥5 cm. Multiphasic CT scan was the means of diagnosis in 82.7% (230/278) of patients, multiphasic MRI in 6.5% (18/278), and liver biopsy in 10.8% (30/278). All patients were discussed, and treatment decisions were made in multidisciplinary team meetings, which were attended by gastroenterologists/hepatologists, pathologists, surgeons with interest in liver surgery, radiologists and medical oncologists. During the period of the study, no liver transplant program existed in Pakistan, and so those who could afford to travel overseas for this procedure did so. Recently, a liver transplant facility has been established in the private sector. All other patients, including those for whom liver transplant was recommended but was not possible for financial reasons, were treated at our institution.

Statistical analysis

Cumulative survival analysis was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The duration of survival was calculated from the time of HCC diagnosis until the death of the patient or last follow-up visit. Log Rank (Mantel Cox) test was used to evaluate the equality of survival distribution for different levels of variables under consideration. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 19, was used to conduct the analysis.

Results

There were 192/278 males in the study, accounting for 69% of the study population. The mean age of the 278 cases was 60.1 ± 9.2 years (range 16-87 years, median 59.5 y). One hundred and eighty-one patients (65.1%) underwent trans-arterial chemo-embolization (TACE). Twenty-three (8.3%) were treated by a combination of TACE plus another modality. These included resection, radio-frequency ablation (RFA), percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI), or the tyrosine kinase inhibitor, sorafenib. Twelve patients (4.3%) underwent ablation procedures (RFA/PEI), while 6 (2.2%) underwent surgical resection. Fourteen patients (5 %) received sorafenib alone, while 42 (15.1%) were deemed suitable for supportive care only.

| Parameter | Median Survival (months) | Parameters with survival comparison | Chi-sq. (df); P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Type | |||

| TACE | 24.6 | TACE & other treatment | 9.05 (1) 0.003 |

| Surgical resection | 31.5 | TACE & surgical resection | 1.89 (1) 0.168 |

| Ablation (PEI, RFA) | 60.7 | TACE & ablation | 3.90 (1) 0.048 |

| TACE with other treatment (Resection RFA,PEI, Sorafenib) | 44 | TACE & Sorafenib | 1.22 (1) 0.26 |

| Sorafenib | 9.6 | TACE & Supportive care | 123.7(1) <0.001 |

| Supportive care | 3.5 | ||

| Focality | |||

| Unifocal | 26.7 | Between unifocal & multifocal | 6.89 (1) 0.009 |

| Multifocal | 17.4 | ||

| Tumour Size | |||

| Up to 3cm | 33.1 | Up to 3 & >5 | 10.03 (1) 0.002 |

| From 3-5 cm | 23.9 | >3-5 & >5 | 5.86 (1) 0.015 |

| >5cm | 16.1 | ||

| Child’s classification | |||

| A | 25.4 | Child’s A & B | 12.79 (1) <0.001 |

| B | 8.8 | Child’s A & C | 198.3 (1) <0.001 |

| C | 1.6 | Child’s B & C | 18.1 (1) <0.001 |

| BCLC stage | |||

| A | 30.5 | BCLC A & B | 7.14 (1) 0.008 |

| B | 21.1 | BCLC A & C | 41.28 (1) <0.001 |

| C | 3.77 | BCLC A & D | 99.7 (1) <0.001 |

| D | 1.67 | BCLC B & C | 26.4 (1) <0.001 |

| BCLC B & D | 92.6 (1) <0.001 | ||

| BCLC C & D | 6.9 (1) 0.008 | ||

| AFP | |||

| ≤299 | 24.8 | ≤ 299 & ≥ 300 | 3.05 (1) 0.081 |

| ≥ 300 | 14.9 | ||

| Overall survival | 23.9 |

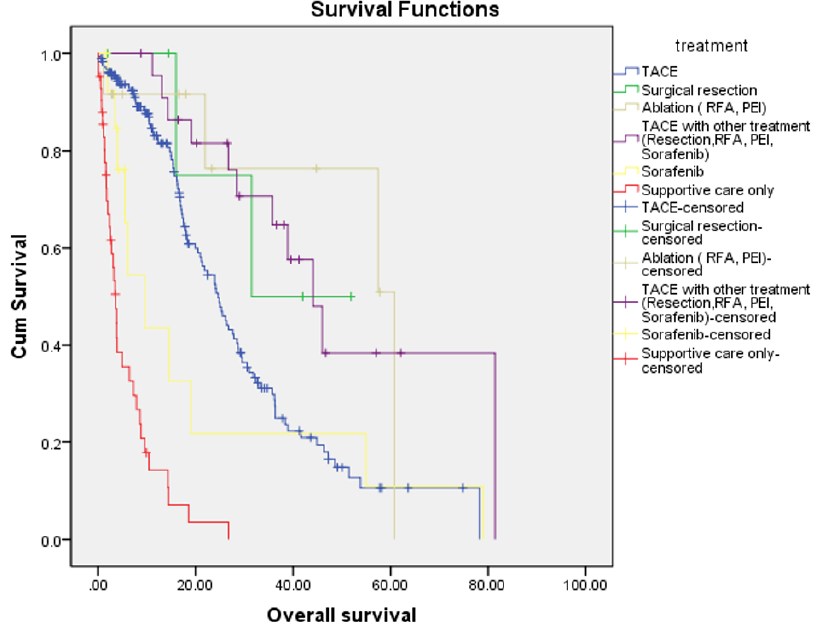

Overall survival for the entire cohort was 23.9 months. The median survival of patients who had an ablative procedure was 61 months, while in those who had TACE in combination with another treatment modality, it was 44 months. Median survival was 31.5 months for those undergoing surgical resection, 24.6 months in those who underwent TACE, 9.6 months in those treated with sorafenib, and 3.6 months for those on supportive care. There were significant differences in survival when patients who underwent TACE alone were compared with those who had either TACE in combination with other treatments (such as resection, RFA, PEI or sorafenib) or an ablative procedure (such as RFA or PEI) (Chi-sq.=3.90, p=0.048). However, when other treatments were compared with TACE, the difference in survival was not significant; Figure 1 shows survival from TACE versus surgical resection or sorafenib. Patients with unifocal tumors (140, 50.4%) had a significantly better median overall survival of 26.7 months, compared to 17.4 months for those with multifocal tumors (138 patients, 49.6%) (Figure 2). Overall, there was a significant difference in survival by tumor size (Chi-sq.=12.61, df=2, p=0.002). Sub-group analysis showed a significant difference in survival between patients with tumor size up to 3 cm and those with size >5 cm (Chi-sq.=10.03, df=1, p=0.002), as well as when comparing those with tumor size 3-5 cm and >5 cm (Chi-sq.=5.86, df=1, p=0.015) (Figure 2). There were significant differences in survival according to the Child-Pugh status, between Child-Pugh class A & B (Chi-sq.=12.79, df=1, p<0.001), A & C (Chi-sq.=198.3, df=1, p<0.001), and B & C (Chi-sq.=18.18, df=1, p<0.001). Similarly, differences between BCLC stage A & B, A & C, and A & D, as well as between B & C, B & D, and C & D were all statistically significant (p-values between <0.001 and 0.008) (Figure 3). Table 2 shows the Chi-square values and p-values for the differences mentioned above.

Several other parameters were also subjected to univariate analysis but were not found to be significant. These included AFP values, for which we used values ≤ 299 and ≥300 as cut-off values (p=0.081). Similarly, the difference in survival by risk factor was also not significant (p=0.14). However, there was a significant association between categories of AFP level (<200 and >/=200) and tumor size (up to 3 cm, >3 cm, 3-5 cm, and >5 cm.); Chi-sq.=9.45, df=2, p=0.009.

Discussion

About 4.8% of the Pakistani population is estimated to be infected with hepatitis C, mainly genotype 3a, and another 2.5% are estimated to have chronic hepatitis B infection10,11. The incidence of HCC in Pakistan in males is about 7.5 per 100,000, while for females this estimate is 2.8 per 100,000 persons per year12,13. About 60-70% of these patients with HCC are infected with hepatitis C, another 20% are infected with hepatitis B, while other causes account for only 10-15% of cases14,15.

In our study, 236 patients (84.8%) had a prior infection with hepatitis C. Although 234 patients (84%) were in Child-Pugh class A at the time of diagnosis, nearly half of the patients (138 or 49.6%) had multifocal tumors at presentation. The majority of our patients had advanced disease with poor clinical status and liver function, as evidenced by intermediate BCLC stage B in 144 patients (51.8%), and were candidates for TACE only. Indeed, 95 (34.2%) presented with BCLC stage A, while 39 (14%) had BCLC C and D, and only 95 (34.2%) were diagnosed as BCLC stage A. Of the 95 patients in BCLC stage A, only 6 patients (2.2%) were judged suitable for surgical resection since many patients with apparently resectable lesions had evidence of portal hypertension, as shown by the presence of varices, platelet count of <100,000, or hepatic venous pressure gradient of >12 mm Hg. Only 12 (4.3%) patients underwent ablative procedures because of tumor location, size or other technical issues, resulting in a huge number of patients undergoing TACE.

Median survival with various treatments was 23.9 months, while it was 24.6 months with TACE. Ablative procedures and surgery were associated with better survival of 61 months versus 31.5 months. This improved survival did not reach statistical significance, possibly because of the small numbers of patients in these two groups. Patients with small tumor size, up to 3 cm, had better survival (p=0.002), which is in keeping with prior studies. In the study by Grieco et al., in which 95.9% of patients had liver cirrhosis, the mean duration of survival of the total study population was 25.7 months. Moreover, the authors noted that the absence of portal vein thrombosis, small tumor size, and low bilirubin levels were significantly correlated with survival; p= 0.006, 0.016 and 0.012, respectively16. Similarly, other studies have also shown a worse prognosis in those with multiple tumors and increasing tumor size, irrespective of vascular invasion17,18. In the study by Ueno et al., which had a higher percentage of patients without cirrhosis (19.2%), the mean survival was also higher, at 37.7 months19. Studies have also shown that there is a correlation between serum AFP levels and microvascular invasion, as well as tumor size20,21.

There is high mortality in patients who develop HCC in the context of co-existent hepatitis B and HIV. The incidence and mortality of HCC have been increasing slowly in areas of low incidence and decreasing in areas of high incidence. However, the WHO data shows a progressive increase in the number of patients diagnosed with primary liver cancer from 437,408 in 1990 to 716,600 in 200222.

In a study of 645 patients with HCC in Pakistan, 82.9% of patients were diagnosed to have HCC only when they became symptomatic, while only 8.2% were diagnosed on screening. This explains why the majority of our patients present with advanced, often multifocal disease. The absence of a national screening program means that this situation is unlikely to change soon. Even for those fortunate enough to be diagnosed early, the absence of a national liver transplant program significantly limits treatment options15. Most patients in our series presented with advanced liver disease with multifocal tumors and were candidates for palliative treatment only.

Conclusions

There is an urgent need for public education to minimize hepatitis B and C transmission, a nationwide screening program to detect disease at an earlier stage, and the development of specialist liver units and liver transplant programs. These are especially needed in high endemic areas of the world with hepatitis B and C, which are mostly developing countries with low educational status and significant recourse constraints.

Abbreviations

AASLD: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

AFP: Alpha fetoprotein

BCLC: Barcelona clinic liver cancer

CT: Computerized tomography

DM: Diabetes mellitus

DNA: Deoxyribonucleic acid

EASL: European Association for the Study of the Liver

HBV: Hepatitis B virus

HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma

HCV: Hepatitis C virus

MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging

PCR: Polymerase chain reaction

PEI: Percutaneous ethanol injection

RFA: Radiofrequency ablation

RNA: Ribonucleic acid

SD: Standard deviation

TACE: Transarterial chemoembolization

WHO: World health organization

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors' Contributions

All authors contributed significantly in this research paper. Hala Mansoor, Muhammad Adnan Masood and Kashif Siddique were involved in acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, as well in drafting the article and rewriting after critical analysis. Farhana Badar and Muhammed Aasim Yusuf were involved in data analysis and in critical review of thbe paper including the final proof version.

References

-

Yang

J.D.,

Roberts

L.R.,

Hepatocellular carcinoma: A global view. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

2010;

7

(8)

:

448-58

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Kinoshita

A.,

Onoda

H.,

Imai

N.,

Iwaku

A.,

Oishi

M.,

Tanaka

K.,

The Glasgow Prognostic Score, an inflammation based prognostic score, predicts survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer.

2013;

13

(1)

:

52

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Parkin

D.M.,

Bray

F.,

Ferlay

J.,

Pisani

P.,

Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin.

2005;

55

(2)

:

74-108

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

El-Serag

H.B.,

Hepatocellular carcinoma: recent trends in the United States. Gastroenterology.

2004;

127

(5)

:

27-34

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Morgan

T.R.,

Mandayam

S.,

Jamal

M.M.,

Alcohol and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology.

2004;

127

(5)

:

87-96

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Gomaa

A.I.,

Khan

S.A.,

Toledano

M.B.,

Waked

I.,

Taylor-Robinson

S.D.,

Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology, risk factors and pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol.

2008;

14

(27)

:

4300-8

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Singal

A.G.,

Pillai

A.,

Tiro

J.,

Early detection, curative treatment, and survival rates for hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in patients with cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. PLoS Med.

2014;

11

(4)

:

e1001624

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Cabibbo

G.,

Enea

M.,

Attanasio

M.,

Bruix

J.,

Crax\`\i

A.,

Cammà

C.,

A meta-analysis of survival rates of untreated patients in randomized clinical trials of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology.

2010;

51

(4)

:

1274-83

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Yusuf

M.A.,

Badar

F.,

Meerza

F.,

Khokhar

R.A.,

Ali

F.A.,

Sarwar

S.,

Survival from hepatocellular carcinoma at a cancer hospital in Pakistan. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev.

2007;

8

(2)

:

272-4

.

PubMed Google Scholar -

Abbas

Z.,

Jafri

W.,

Hamid

S.,

Pakistan Society for the Study of Liver Diseases

Management of hepatitis B: Pakistan Society for the Study of Liver Diseases (PSSLD) practice guidelines. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak.

2010;

20

(3)

:

198-201

.

PubMed Google Scholar -

Qureshi

H.,

Bile

K.M.,

Jooma

R.,

Alam

S.E.,

Afridi

H.U.,

Prevalence of hepatitis B and C viral infections in Pakistan: findings of a national survey appealing for effective prevention and control measures. East Mediterr Health J.

2010;

16

:

15-23

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Bhurgri

Y.,

Bhurgri

A.,

Pervez

S.,

Bhurgri

M.,

Kayani

N.,

Ahmed

R.,

Cancer profile of Hyderabad, Pakistan 1998-2002. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev.

2005;

6

(4)

:

474-80

.

PubMed Google Scholar -

Bhurgri

Y.,

Pervez

S.,

Kayani

N.,

Bhurgri

A.,

Usman

A.,

Bashir

I.,

Cancer profile of Larkana, Pakistan (2000-2002). Asian Pac J Cancer Prev.

2006;

7

(4)

:

518-21

.

PubMed Google Scholar -

Butt

A.S.,

Hamid

S.,

Wadalawala

A.A.,

Ghufran

M.,

Javed

A.A.,

Farooq

O.,

Hepatocellular carcinoma in Native South Asian Pakistani population; trends, clinico-pathological characteristics & differences in viral marker negative & viral-hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Res Notes.

2013;

6

(1)

:

137

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Butt

A.S.,

Abbas

Z.,

Jafri

W.,

Hepatocellular carcinoma in pakistan: where do we stand?. Hepat Mon.

2012;

12

:

e6023

.

PubMed Google Scholar -

Grieco

A.,

Pompili

M.,

Caminiti

G.,

Miele

L.,

Covino

M.,

Alfei

B.,

Prognostic factors for survival in patients with early-intermediate hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing non-surgical therapy: comparison of Okuda, CLIP, and BCLC staging systems in a single Italian centre. Gut.

2005;

54

(3)

:

411-8

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Minagawa

M.,

Ikai

I.,

Matsuyama

Y.,

Yamaoka

Y.,

Makuuchi

M.,

Staging of hepatocellular carcinoma: assessment of the Japanese TNM and AJCC/UICC TNM systems in a cohort of 13,772 patients in Japan. Ann Surg.

2007;

245

(6)

:

909-22

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Nathan

H.,

Schulick

R.D.,

Choti

M.A.,

Pawlik

T.M.,

Predictors of survival after resection of early hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg.

2009;

249

(5)

:

799-805

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Ueno

S.,

Tanabe

G.,

Sako

K.,

Hiwaki

T.,

Hokotate

H.,

Fukukura

Y.,

Discrimination value of the Western prognostic system (CLIP score) for hepatocellular carcinoma in 662 Japanese patients. Hepatology.

2001;

34

(3)

:

529-34

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Abbasi

A.,

Bhutto

A.R.,

Butt

N.,

Munir

S.M.,

Corelation of serum alpha fetoprotein and tumor size in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Pak Med Assoc.

2012;

62

(1)

:

33-6

.

PubMed Google Scholar -

McHugh

P.P.,

Gilbert

J.,

Vera

S.,

Koch

A.,

Ranjan

D.,

Gedaly

R.,

Alpha-fetoprotein and tumour size are associated with microvascular invasion in explanted livers of patients undergoing transplantation with hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB (Oxford).

2010;

12

(1)

:

56-61

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

El-Serag

H.B.,

Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology.

2012;

142

(6)

:

1264-1273

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar

Comments

Downloads

Article Details

Volume & Issue : Vol 6 No 11 (2019)

Page No.: 3492-3500

Published on: 2019-11-29

Citations

Copyrights & License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Search Panel

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Search for this article in:

Google Scholar

Researchgate

- HTML viewed - 7161 times

- View Article downloaded - 0 times

- Download PDF downloaded - 1833 times

Biomedpress

Biomedpress