Preclinical toxicological evaluation of measles virus vaccine strain in non-human primates: A two-month intravenous study

- Department of Pathophysiology, Vietnam Military Medical University, Hanoi, Viet Nam

- Department of Biochemistry, 103 Military Medical Hospital, Vietnam Military Medical University, Hanoi, Viet Nam

- Institute of Biomedicine & Pharmacy, Vietnam Military Medical University, Hanoi, VietNam

- Centre for Research and Production of Vaccines and Biology (POLYVAC), Hanoi, Viet Nam

- Department of Pathology, 103 Military Medical Hospital, Vietnam Military Medical University, Hanoi, Viet Nam

- Department of Neurology, Military Hospital 103, Vietnam Military Medical University

- Military Institute of Clinical Embryology and Histology, Vietnam Military Medical University, Hanoi, Vietnam

- nstitute of Biomedicine & Pharmacy, Vietnam Military Medical University, Hanoi, VietNam

Abstract

Introduction: Based on its ability to kill tumor cells, the vaccine strain of the measles virus is used for oncolytic virotherapy. However, the dose required for cancer therapy is much higher than that used for vaccination. Therefore, this study was conducted to evaluate the preclinical toxicology of the vaccine strain of measles virus in monkeys.

Methods: 16 healthy Macaca mulata monkeys were randomly divided into four groups, of which one was a control. A preclinical safety evaluation of the vaccine strain of the measles virus was performed, and the three experimental groups were intravenously injected with the strain at doses of 105 TCID50, 106 TCID50 and 107 TCID50 respectively.

Results: There were no significant abnormalities in the physical, clinical, haematological, and biochemical parameters following the intravenous injection with measles vaccine at doses of 105 TCID50, 106 TCID50 and 107 TCID50. The vaccine strain of measles virus remained in the plasma until the 30th day and disappeared on the 60th, and it did not persist in the tissues on days 30 and 60 post injection. Measles IgG antibody was negative on days 0, 1, 3, and 8 and was positive on days 15, 30, and 60 post administration of the measles virus. The histopathology of target organs was not affected in all groups on days 30 and 60 post injection.

Conclusions: The systematic preclinical safety data of the present study confirms the safety of two months of concentrated measles vaccine administration in the Macaca mulata monkey for clinical trials.

Introduction

Oncolytic viruses (OLVs) have been used to effectively treat several cancers due to their ability to replicate and break down cancer cells and/or stimulate the immune system to respond against tumours1. Recently, many vaccines for preventing infectious diseases have been repurposed for use in cancer treatments, of which the measles vaccine strain has shown great potential in anticancer activities against different malignancies2. The effectivness of OLVs in cancer treatment has been established in preclinical studies and clinical trials, and several OLVs have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for clinical practice3. The vaccine strain of the measles virus (MeV) is one of the most highly effective OLVs for cancer treatment. MeV has previously been shown to have a great anticancer property in small animal models against different cancers such as laryngeal cancer4, human solid malignancies5, and human hematological cancers6. However, the MeV dose required for cancer treatment is much higher than that used for vaccination. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate the preclinical safety and immunogenicity of the high-dose vaccine in experimental animals before employing the same in clinical practice.

Attenuated MeV preparations are safe for the community and have been used as vaccines for over 50 years7. In Vietnam, the Centre for Research and Production of Vaccines and Biologicals (POLYVAC) has been producing effective, high-dose MeV vaccines that meet community cancer treatment requirements and standards.

The attenuated MeV strains use the CD46 receptor to enter both human and monkey cells. Studies have showed that the measles infection process in monkeys is similar to that in humans7; therefore, monkeys are the most suitable animals for evaluating the safety and efficacy of the measles vaccine. Accordingly, the present study was conducted to evaluate the preclinical safety of MeV in monkeys by assessing the physical, clinical and histopathological profiles of the target organs.

Methods

Ethical statement

All experimental animal procedures were conducted according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use guidelines. The study protocols were approved by the Ethical Committee of the Vietnam Military Medical University (VMMU).

Vaccine strain of measles virus

The vaccine strain of MeV was produced by POLYVAC. Live measles vaccine of the AIK-C strain was produced in Vietnam, according to the technology transfer from the Kitasato Institute, Japan. Moreover, the vaccines produced by POLYVAC (PolyVac I and II) showed a high immunogenicity in two clinical trials in Vietnam8. The vaccine used for cancer treatment purpose was concentrated at doses of 10 TCID50, 10 TCID50, 10 TCID50.

Study design

The research was carried out at Rua Island in Bai Tu Long Bay, Cam Pha City, Quang Ninh Province, particularly at the Department of Pathophysiology of Vietnam Military Medical University from August 2019 to May 2020. 16 monkeys () of 2 years of age that weighed 2.5 ± 0.2 kg and were negative with measles IgG antibodies (confirmed by ELISA) were chosen for this study, irrespective of sex. The monkeys were raised in semi-natural conditions, kept in separate houses, and fed appropriate diets. During the quarantine period, monkeys were fed with peanuts, fresh vegetables, and seasonal fruits. They were then equally and randomly divided into four groups: one control group and three experimental groups that were injected with the measles vaccine at doses of 10 TCID50, 10 TCID50, 10 TCID50 respectively. All the monkeys were administered a single dose through the small saphenous vein. Data on the study parameters were collected before injection (day 0) and on days 1, 3, 8, 15, 30 and 60 post injection. On day 30 and 60 post injection, eight animals were randomly selected (two per group/dose) and given an intramuscular injection of ketamine HCl [15 mg/kg]), following which they were euthanised (administering thiopentone sodium [100 mg/kg]). Tissues were collected from various organs, including the brain, salivary, lungs, heart, liver, kidneys, and spleen, for histopathological examination and measles virus detection.

Overall health status

The animals were checked and examined for behavioural abnormalities daily, and their body weights and temperatures were recorded. Skin, mucosa, and conjunctiva were observed and examined for any abnormalities in the morning at each timepoint.

Clinical laboratory investigations

Blood samples were collected on days 0 and 1, 3, 8, 15, 30, and 60 post injection. The haematology profile included red blood cell (RBC), total white blood cell (WBC), and platelet counts as well as haemoglobin (Hb) levels. The parameters were analysed via an automated blood cell counter (Sysmex haematology testing machine, USA) using blood samples collected in EDTA K2 tubes. The laboratory parameters included plasma glucose, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, total protein, albumin, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and cholinesterase; these were estimated using an autoanalyser (AU640, Beckman Coulter, USA). The quality control samples supplied by Wipro Biomed were used to establish the precision and accuracy of the analyses.

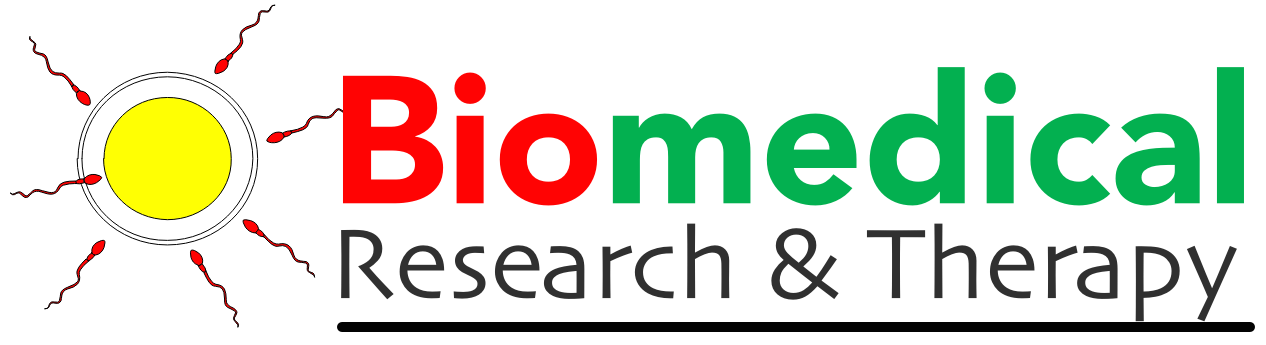

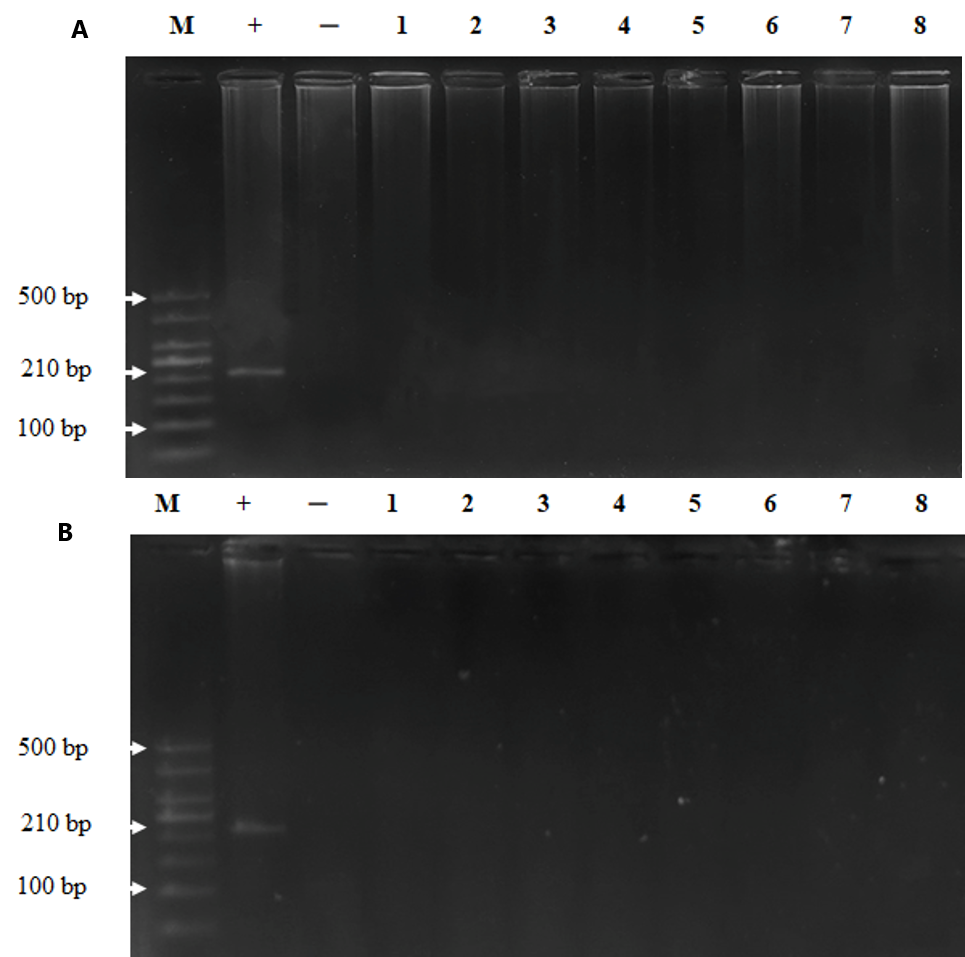

Nested PCR for detection of measles virus in plasma and tissues

For MeV detection, plasma samples of the monkeys on days 1, 3, 8, 15, 30 and 60 post injection and tissue samples from the brain, salivary, lungs, heart, liver, kidneys, and spleen on days 30 and 60 post injection were collected. Total RNA was isolated from the plasma and tissues using an RNA purification kit (Thermo Scientific, K0731) and employed as a template for cDNA synthesis using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific, K1622). The synthesised cDNA was subsequently subjected to nested RT-PCR. The first-step of RT-PCR using primers (NBE-MAS: 5’-GAT CCA GAC TTC TGG CCG G-3’ and NDE-MAS: GAA TCA GCT GCC GTG TCT GG-3’) amplified a 430-bp fragment of DNA. The second step of the PCR using another set of primers (NAE-MAS: 5’-GGA GTC TCC AGG TCA ATT GA-3’ and NCE-MAS: 5’-TCC TTG TTC TCG AAC CAT CC-3’) amplified a 250-bp fragment. PCR reactions were performed at Agilent Technologies SureCycler 8800 (Malaysia) using a DreamTag Hot Start PCR Master Mix (Thermo Scientific, K9011), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Thermal conditions for the first step of the nested PCR involved denaturation at 94 °C for 4 minutes and then at 94 °C for 35 cycles of 30 seconds, annealing at 52 C for 35 seconds, and extension at 72 C for 45 seconds. Thermal conditions for the second step involved denaturation at 94 °C for 4 minutes and then at 94 °C for 40 cycles of 30 seconds, annealing at 50 C for 35 seconds, and extension at 72 C for 45 seconds. A polishing cycle at 72 °C for 5 minutes was used for the final extension. Amplicons were separated in 2% agarose gels with TBE buffer and visualised via GoldView staining (Solarbio, China). A 50-bp DNA ladder (New England, Biolab, N3236S) was used as the molecular weight marker.

Detection of measles virus-specific IgG antibody

We used the Monkey Measles Virus Antibody IgG ELISA Kit (Melsin, EKMON-0083, China) to detect measles IgG antibody in monkey serum pre-experiment and on days 1, 3, 8, 15, 30 and 60 post injection. The samples, positive control, negative control, and HRP-conjugated antibody were added to each well of the provided microtiter plate, which had been pre-coated with antigen. After incubation and washing to remove the unbinding enzyme, chromogen solutions A and B were added. The OD was spectrophotometrically measured at a wavelength of 450/560 nm. The presence of MeV IgG antibody in the samples was then determined by comparing the OD of the samples with the cut-off values.

The pathological examinations

The brain, salivary, lungs, heart, liver, kidneys, and spleen of the monkeys in each group on days 30 and 60 post injection were collected and preserved in 10% buffered neutral formalin. After a minimum of 24 hours of fixation, they were sampled and processed; paraffin blocks were made and 4 μm sections obtained. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and examined under a light microscope. All deviations from normal histology were recorded and compared with the corresponding controls.

Statistical analysis

For the quantitative variables, mean and variance were calculated. The values before and after the concentrated measles vaccine injection were compared using a paired sample t-test; the values of each group were compared by using ANOVA. For all the statistical tests, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Body weights of monkeys (kg)

|

Groups |

Days | |||||

|

0 |

3 |

8 |

15 |

30 |

60 | |

|

Control |

2.2 ± 0.18 (4) |

2.2 ± 0.18 (4) |

2.3 ± 0.17 (4) |

2.4 ± 0.10 (4) |

2.4 ± 0.08 (4) |

2.6 (2) |

|

105 TCID50 |

2.5 ± 0.41 (4) |

2.2 ± 0.18 (4) |

2.5 ± 0.29 (4) |

2.4 ± 0.40 (4) |

2.4 ± 0.41 (4) |

3.1 (2) |

|

106 TCID50 |

2.2 ± 0.13 (4) |

2.3 ± 0.13 (4) |

2.3 ± 0.16 (4) |

2.3 ± 0.26 (4) |

2.4 ± 0.22 (4) |

2.9 (2) |

|

107 TCID50 |

2.4 ± 0,15 (4) |

2.3 ± 0.15 (4) |

2.4 ± 0.15 (4) |

2.4 ± 0.08 (4) |

2.5 ± 0.10 (4) |

2.7 (2) |

Body temperature of monkeys (℃)

|

Groups |

Days | ||||||

|

0 |

1 |

3 |

8 |

15 |

30 |

60 | |

|

Control |

39.0 ± 0.13 (4) |

39.2 ± 0.19 (4) |

38.4 ± 0.52 (4) |

38.6 ± 0.45 (4) |

38.8 ± 0.83 (4) |

38.9 ± 0.48 (4) |

39.3 (2) |

|

105 TCID50 |

39.1 ± 0.28 (4) |

39.6 ± 0.65 (4) |

39.2 ± 0.69 (4) |

39.1 ± 0.95 (4) |

39.2 ± 0.77 (4) |

39.5 ± 0.94 (4) |

39.6 (2) |

|

106 TCID50 |

39.1 ± 0.21 (4) |

39.2 ± 0.22 (4) |

39.4 ± 0.44 (4) |

39.0 ± 0.51 (4) |

39.2 ± 0.26 (4) |

39.8 ± 0.50 (4) |

39.3 (2) |

|

107 TCID50 |

39.3 ± 0.28 (4) |

39.3 ± 0.51 (4) |

39.5 ± 0.37 (4) |

39.4 ± 0.59 (4) |

39.6 ± 0.31 (4) |

39.7 ± 0.36 (4) |

39.7 (2) |

Hematological parameters of monkeys

|

Parameters |

Days |

Groups | |||

|

Control |

105 TCID50 |

106 TCID50 |

107 TCID50 | ||

|

RBC x 106 /µL |

0 |

6.2 ± 0.73 (4) |

6.5 ± 0.87 (4) |

6.0 ± 0.49 (4) |

5.9 ± 0.16 (4) |

|

1 |

5.9 ± 0.43 (4) |

5.6 ± 0.32 (4) |

5.9 ± 0.42 (4) |

5.7 ± 0.20 (4) | |

|

3 |

5.9 ± 0.38 (4) |

5.5 ± 0.32 (4) |

5.7 ± 0.46 (4) |

5.6 ± 0.41 (4) | |

|

8 |

5.5 ± 0.41 (4) |

5.4 ± 0.25 (4) |

5.6 ± 0.57 (4) |

5.2 ± 0.40 (4) | |

|

15 |

6.2 ± 0.50 (4) |

6.5 ± 1.05 (4) |

6.6 ± 1.09 (4) |

6.2 ± 1.02 (4) | |

|

30 |

6.7 ± 0.73 (4) |

6.8 ± 1.66 (4) |

6.6 ± 1.19 (4) |

6.9 ± 1.13 (4) | |

|

60 |

6.3 (2) |

6.4 (2) |

6.3 (2) |

6.9 (2) | |

|

WBC x 103/µL |

0 |

12.8 ± 4.40 (4) |

12.3 ± 5.80 (4) |

11.2 ± 1.39 (4) |

12.6 ± 5.52 (4) |

|

1 |

11.7 ± 4.81 (4) |

12.9 ± 6.72 (4) |

12.7 ± 3.66 (4) |

12.1 ± 5.16 (4) | |

|

3 |

13.7 ± 5.08 (4) |

13.2 ± 3.39 (4) |

13.8 ± 2.53 (4) |

12.8 ± 4.98 (4) | |

|

8 |

13.4 ± 8.37 (4) |

11.2 ± 1.40 (4) |

12.3 ± 3.46 (4) |

13.5 ± 4.09 (4) | |

|

15 |

13.9 ± 5.33 (4) |

13.1 ± 3.78 (4) |

13.3 ± 3.88 (4) |

13.6 ± 2.59 (4) | |

|

30 |

12.6 ± 3.86 (4) |

13.2 ± 3.84 (4) |

13.2 ± 4.55 (4) |

12.7 ± 4.45 (4) | |

|

60 |

12.9 (2) |

13.0 (2) |

11.1 (2) |

11.7 (2) | |

|

Platelets x 103 /µL |

0 |

346.0 ± 86.80 (4) |

414.5 ± 62.81 (4) |

353.0 ± 121.52 (4) |

440.2 ± 154.73 (4) |

|

1 |

348.0 ± 58.72 (4) |

418.3 ± 87.20 (4) |

394.3 ±108.27 (4) |

462.7 ± 131.18 (4) | |

|

3 |

364.5 ± 80.32 (4) |

438.5 ± 98.02 (4) |

391.0 ± 97.06 (4) |

426.5 ± 129.43 (4) | |

|

8 |

390.5 ± 79.82 (4) |

492.8 ± 161.62 (4) |

424.3 ± 71.30 (4) |

420.0 ± 174.01 (4) | |

|

15 |

378.0 ± 46.20 (4) |

409.8 ± 128.23 (4) |

336.5 ± 164.81 (4) |

454.5 ± 151.92 (4) | |

|

30 |

324.5 ± 98.27 (4) |

470.2 ± 107.60 (4) |

398.5 ± 105.07 (4) |

401.2 ± 129.99 (4) | |

|

60 |

347.5 (2) |

378.0 (2) |

349.5 (2) |

422.5 (2) | |

|

Hemoglobin (g/l) |

0 |

143.8 ± 15.02 (4) |

147.5 ± 17.43 (4) |

139.8 ± 8.32 (4) |

134.8 ± 3.43 (4) |

|

1 |

135.8 ± 15.02 (4) |

126.5 ± 2.86 (4) |

134.5 ± 6.53 (4) |

129.8 ± 2.27 (4) | |

|

3 |

136.0 ± 11.05 (4) |

125.3 ± 3.75 (4) |

131.5 ± 7.13 (4) |

128.0 ± 3.73 (4) | |

|

8 |

128.8 ± 8.63 (4) |

125.6 ± 3.79 (4) |

131.0 ± 7.32 (4) |

128.0 ± 3.73 (4) | |

|

15 |

147.5 ± 13.33 (4) |

148.5 ± 16.89 (4) |

156.0 ± 21.82 (4) |

159.5 ± 23.82 (4) | |

|

30 |

154.5 ± 10.53 (4) |

151.5 ± 30.63 (4) |

139.8 ± 8.32 (4) |

134.8 ± 3.43 (4) | |

|

60 |

137.0 (2) |

135.0 (2) |

133.5 (2) |

136.5 (2) | |

Electrophoresis image of PCR product of measles virus in monkey plasma. On the day 3 (A) and day 60 (B) post-injection. M is a scale of 50 bp, (+) is positive using RNA from measles virus vaccine, (-) is negative without RNA, (1-2) sample of control group, (3-4) sample of group1 injected at a dose of 105 TCID50; (5-6) samples of group 2 injected at a dose of 106 TCID50; (7-8) samples of group 3 injected at a dose of 107 TCID50, the specific band for measles virus is (210 bp).

Electrophoresis image of PCR product of measles virus in spleen. On the day 30 (A) and day 60 (B) post-injection. M is a scale of 50 bp, (+) is positive using RNA from measles virus vaccine, (-) is negative without RNA, (1-2) sample of control group, (3-4) sample of group 1injected at a dose of 105 TCID50; (5-6) samples of group 2 injected at a dose of 106 TCID50; (7-8) samples of group 3 injected at a dose of 107 TCID50, the specific band for measles virus is (210 bp).

The histopathological examination of brain, salivary, lungs, heart, liver, kidney, and spleen of the control group and measles administration group at 30 day post-injection.

The histopathological examination of brain, salivary, lungs, heart, liver, kidney, and spleen of control group and measles administration group at 60 day post-injection.

Results

Overall health status

The physical activity and health statuses of monkeys infected with different doses of MeV (10–10TCID50) were examined. The results did not reveal any significant changes in body weight (

Clinical laboratory investigations

The health status of each of the monkeys was examined by checking the laboratory parameters. The results showed that the haematological (

The presence of measles virus in plasma and tissues

To examine whether MeV was persistent in the bodies of the monkeys post injection, we took plasma and tissue samples for viral detection via nested RT-PCR. The results demonstrated that MeV was present in the plasma of the monkeys until day 30 post injection and disappeared on day 60 (Figure 1). MeV was not present in the tissues of monkeys on day 30 or day 60 after intravenous injection (Figure 2). These results indicate that the monkeys were infected with MeV, and the viruses circulated for one month after the infection.

Chemical parameters of monkeys

|

Parameters |

Days |

Groups | |||

|

Control |

105 TCID50 |

106 TCID50 |

107 TCID50 | ||

|

Glucose (mmol/l) |

0 |

5.9 ± 1.03 (4) |

5.4 ± 1.58 (4) |

5.1 ± 1.36 (4) |

5.0 ± 0.82 (4) |

|

1 |

5.7 ± 1.29 (4) |

5.6 ± 0.62 (4) |

5.0 ± 1.48 (4) |

5.4 ± 1.75 (4) | |

|

3 |

5.9 ± 1.66 (4) |

5.5 ± 2.43 (4) |

5.2 ± 0.85 (4) |

4.9 ± 1.06 (4) | |

|

8 |

4.9 ± 0.98 (4) |

5.0 ± 0.24 (4) |

5.7 ± 0.53 (4) |

4.9 ± 0.50 (4) | |

|

15 |

4.9 ± 0.81 (4) |

5.8 ± 1.10 (4) |

4.8 ± 1.98 (4) |

4.7 ± 1.15 (4) | |

|

30 |

5.0 ± 0.36 (4) |

5.0 ± 0.69 (4) |

5.0 ± 0.45 (4) |

4.7 ± 0.59 (4) | |

|

60 |

5.6 (2) |

5.3 (2) |

5.1 (2) |

5.0 (2) | |

|

Ure (mmol/l) |

0 |

6.1 ± 0.28 (4) |

6.1 ± 0.28 (4) |

6 .9 ±2.31 (4) |

6.6 ± 1.23 (4) |

|

1 |

6.3 ± 1.28 (4) |

6.9 ± 1.27 (4) |

6.5 ± 1.73 (4) |

6.5 ± 1.49 (4) | |

|

3 |

6.8 ± 1.11 (4) |

6.8 ± 1.13 (4) |

6.8 ± 0.90 (4) |

6.2 ± 0.87 (4) | |

|

8 |

6.4 ± 0.59 (4) |

6.5 ± 1.68 (4) |

7.2 ± 1.28 (4) |

6.3 ± 1.61 (4) | |

|

15 |

6.5 ± 1.72 (4) |

6.5 ± 1.85 (4) |

7.4 ± 1.36 (4) |

6.5 ± 1.11 (4) | |

|

30 |

6.1 ± 0.64 (4) |

7.1 ± 2.14 (4) |

6.4 ± 1.73 (4) |

7.0 ± 1.17 (4) | |

|

60 |

6.4 (2) |

7.2 (2) |

7.1 (2) |

6.4 (2) | |

|

Creatinine (µmol/l) |

0 |

73.4 ± 3.83 (4) |

83.3 ± 10.49 (4) |

80.1 ± 5.21 (4) |

72.3 ± 13.25 (4) |

|

1 |

78.9 ± 5.25 (4) |

87.4 ± 6.61 (4) |

79.8 ± 4.59 (4) |

81.8 ± 8.33 (4) | |

|

3 |

75.3 ± 7.05 (4) |

81.0 ± 8.30 (4) |

75.4 ± 6.16 (4) |

81.2 ± 9.17 (4) | |

|

8 |

76.5 ± 6.23 (4) |

84.7 ± 7.41 (4) |

82.9 ± 5.41 (4) |

80.4 ± 6.00 (4) | |

|

15 |

74.5 ± 1.36 (4) |

74.6 ± 6.58 (4) |

77.9 ± 13.11 (4) |

72.5 ± 6.93 (4) | |

|

30 |

79.1 ± 3.94 (4) |

77.6 ± 67.39 (4) |

77.3 ± 12.87 (4) |

74.2 ± 6.43 (4) | |

|

60 |

70.6 (2) |

70.2 (2) |

71.1 (2) |

78.9 (2) | |

|

Protein (g/l) |

0 |

77.0 ± 2.02 (4) |

74.6 ± 4.50 (4) |

77.8 ± 9.06 (4) |

73.9 ± 5.11 (4) |

|

1 |

79.0 ± 2.67 (4) |

79.0 ± 5.19 (4) |

72.5 ± 3.25 (4) |

70.9 ± 6.98 (4) | |

|

3 |

72.8 ± 4.89 (4) |

72.8 ± 4.44 (4) |

73.3 ± 2.71 (4) |

72.2 ± 4.75 (4) | |

|

8 |

72.1 ± 1.17 (4) |

70.7 ± 5.20 (4) |

74.4 ± 3.88 (4) |

74.6 ± 8.06 (4) | |

|

15 |

74.3 ± 5.30 (4) |

71.9 ± 3.09 (4) |

75.6 ± 0.92 (4) |

75.1 ± 5.30 (4) | |

|

30 |

71.3 ± 3.38 (4) |

71.3 ± 1.62 (4) |

70.6 ± 4.15 (4) |

73.63 ± 3.46 (4) | |

|

60 |

69.3 (2) |

70.3 (2) |

73.7 (2) |

70.7 (2) | |

|

Albumin (g/l) |

40.7±5.12 (4) |

45.2 ± 1.62 (4) |

46.3 ± 5.10 (4) |

41.9 ± 3.54 (4) | |

|

1 |

42.6±4.42 (4) |

42.5 ± 2.34 (4) |

41.7 ± 3.34 (4) |

41.5 ± 4.38 (4) | |

|

3 |

42.2±1.88 (4) |

43.3 ± 2.75 (4) |

42.5 ± 2.46 (4) |

40.1 ± 1.65 (4) | |

|

8 |

41.7±1.82 (4) |

42.7 ± 3.48 (4) |

43.7 ± 3.12 (4) |

40.7 ± 3.10 (4) | |

|

15 |

43.7±2.88 (4) |

44.4 ± 1.80 (4) |

45.5 ± 2.49 (4) |

44.7 ± 0.89 (4) | |

|

30 |

40.9±6.64 (4) |

45.1 ± 1.83 (4) |

45.1 ± 2.49 (4) |

40.1 ± 2.75 (4) | |

|

60 |

39.5 (2) |

40.2 (2) |

45.1 (2) |

46.9 (2) | |

|

AST (U/l) |

0 |

56.1 ± 9.23 (4) |

57.1 ± 13.04 (4) |

53.2 ± 7.40 (4) |

53.2 ± 5.19 (4) |

|

1 |

52.4 ± 8.67 (4) |

51.8 ± 4.82 (4) |

54.7 ± 10.92 (4) |

55.8 ± 9.07 (4) | |

|

3 |

55.8 ± 9.07 (4) |

56.2 ± 6.55 (4) |

54.4 ± 9.40 (4) |

57.1 ± 7.66 (4) | |

|

8 |

55.3 ± 7.69 (4) |

55.8 ± 5.82 (4) |

47.9 ± 8.44 (4) |

49.8 ± 9.69 (4) | |

|

15 |

51.7 ± 14.9 (4) |

50.6 ± 2.28 (4) |

55.1 ± 9.28 (4) |

55.3 ± 9.72 (4) | |

|

30 |

51.9 ± 10.40 (4) |

52.5 ± 9.69 (4) |

53.7 ± 3.78 (4) |

52.2 ± 12.7 (4) | |

|

60 |

55.4 (2) |

57.1 (2) |

49.3 (2) |

48.8 (2) | |

|

ALT (U/l) |

0 |

82.7 ± 3.72 (4) |

85.6 ± 3.29 (4) |

86.1 ± 4.35 (4) |

84.3 ± 2.81 (4) |

|

1 |

84.7 ± 3.74 (4) |

83.0 ± 3.04 (4) |

86.9 ± 4.56 (4) |

82.9 ± 2.89 (4) | |

|

3 |

86.2 ± 3.10 (4) |

84.3 ± 2.29 (4) |

86.6 ± 4.96 (4) |

85.7 ± 2.99 (4) | |

|

8 |

82.2 ± 2.70 (4) |

85.9 ± 2.45 (4) |

83.9 ± 4.76 (4) |

86.3 ± 2.99 (4) | |

|

15 |

84.6 ± 1.98 (4) |

84.7 ± 3.79 (4) |

81.9 ± 2.52 (4) |

86.1 ± 3.79 (4) | |

|

30 |

85.3 ± 3.73 (4) |

85.7 ± 3.27 (4) |

83.9 ± 4.36 (4) |

84.85 ± 4.08 (4) | |

|

60 |

84.1 (2) |

80.2 (2) |

80.3 (2) |

83.0 (2) | |

|

Cholinesterase (kU/l) |

0 |

13.3 ± 2.15 (4) |

11.7 ± 1.39 (4) |

11.2 ± 2.60 (4) |

9.7 ± 2.70 (4) |

|

1 |

11.9 ± 1.47 (4) |

10.4 ± 3.04 (4) |

11.6 ± 1.71 (4) |

10.2 ± 1.40 (4) | |

|

3 |

13.8 ± 2.14 (4) |

11.0 ± 1.51 (4) |

9.8 ± 1.63 (4) |

9.7 ± 1.67 (4) | |

|

8 |

10.9 ± 1.26 (4) |

11.1 ± 2.01 (4) |

11.9 ± 1.17 (4) |

11.1 ± 3030 (4) | |

|

15 |

11.4 ± 1.73 (4) |

10.7 ± 1.580 (4) |

12.8 ± 1.98 (4) |

11.0 ± 2.40 (4) | |

|

30 |

11.2 ± 3.91 (4) |

10.0 ± 1.60 (4) |

12.8 ± 0.78 (4) |

10.5 ± 2.90 (4) | |

|

60 |

12.4 (2) |

10.4 (2) |

9.7 (2) |

10.3 (2) | |

Elisa test for Measles IgG antibody detection

|

Group |

Days | |||||

|

0 |

3 |

8 |

15 |

30 |

60 | |

|

Control (positive/total) |

0/4 |

0/4 |

0/4 |

0/4 |

0/4 |

0/2 |

|

105 CID50 (positive/total) |

0/4 |

0/4 |

0/4 |

4/4 |

4/4 |

2/2 |

|

106 TCID50 (positive/total) |

0/4 |

0/4 |

0/4 |

4/4 |

4/4 |

2/2 |

|

107 TCID50 (positive/total) |

0/4 |

0/4 |

0/4 |

4/4 |

4/4 |

2/2 |

The presence of MeV IgG

The vaccine activity of MeV and immune responses of the monkeys were subsequently checked. The MeV-specific IgG antibody was detected, and the results showed that monkeys in the control group were negative for MeV IgG antibody during the study. Monkeys injected with 10 TCID50, 10 TCID50, and 10 TCID50 MeV were negative for MeV IgG antibodies on days 0, 1, 3, and 8 and positive on days 15, 30, and 60 post injection (

Histopathology of target organs

Histiopathology was performed to check whether MeV may caused any damage in different organs (brain, salivary, lungs, heart, liver, kidneys, and spleen) during the persistence of the virus. No significant changes in the histopathology were observed between the control and measles administration groups, although different doses were present in the brain, salivary, lungs, heart, liver, kidneys, and spleen of the monkeys on days 30 (Figure 3) and 60 (Figure 4) post injection. These results suggest that MeV did not damage the organs of infected monkeys.

Discussion

While the safety of attenuated MeV products has been proved, the actual vaccine dose used for cancer treatment is higher than that used for expanded immunization. Preclinical experiments have also demonstrated that extrapolating the data for clinical situations depends on species variation; therefore, species and dose selection constitute the primary requirement in preclinical toxicology studies. Selection of the species varies with the nature of the compound under study. Evaluating the safety of a new biological product depends on the species of the animal used9, 10, affinity and level of receptor distribution with the biological product, dose, and timing employed9. To evaluate the safety of the concentrated measles vaccine, the monkey (non-human primate) species was selected because 95% of this primate’s genome is similar to that of humans; moreover, the anatomical, physiological and immunological characteristics of monkeys are similar to that of humans. Notably, monkeys are highly susceptible to MeV infection and may develop pathological lesions and clinical symptoms similar to MeV infections in humans. A previous study showed that monkeys with MeV infections have some clinical presentations similar to those in humans, including rashes, mucositis and fever11. Our study found that monkeys infected with high doses of MeV showed no significant abnormalities in physical and laboratory examination, suggesting the safety of the MeV vaccine strain for cancer treatment purposes.

The MeV doses administered in this study were 10TCID50, 10TCID50, and 10 TCID50, which made it challenging. The MeV doses have been effectively used for cancer treatment in our previous studies12 and also for human ovarian cancer treatment13, but these are higher than those used for vaccination (10 TCID50). The MeV doses in our study meet the WHO standards for animal vaccine testing practice14. The results showed that there was no effect of MeV on the overall health status and haematological and biochemical parameters. This result is highly consistent with those of previous studies15, 16, 17, 18, indicating the safety of MeV produced by POLYVAC for cancer treatment.

Our results showed that MeV remained in monkey plasma until day 30 post injection. Previous studies have showed that MeV-RNA exists until the recovery stage. The existence of MeV-RNA was first noted in a follow-up study of Zambian children with measles, in their tissues after their recovery from the disease19. Katz (1962) showed that MeV-RNA can be detected from days 4 to 21 in infected monkeys20. Further, a study conducted on monkeys showed that the existence time of MeV depends on the vaccine dose11.

The mechanism by which MeV-RNA persists and the factors needed to eliminate viral RNA are unclear. MeV effectively inhibits the synthesis of IFN and IFN signals in virus-infected cells; this feature contributes to the persistence of MeV-RNA. Domain C of the V protein plays a role in inhibiting IFN synthesis. The transition from type 1 to type 2 in the response of t-lymphocytes, with the production of regulatory t-lymphocytes and cytokines, plays a role in MeV-RNA clearance. The binding of specific antibodies to H proteins reduces the expression of proteins on the surface of virus-infected cells. Antibodies may enhance the existence of MeV-RNA by reducing the apoptosis and immune clearance of infected cells21. Prolonged existence of MeV-RNA is strongly associated with persistent infections and may explain immunological abnormalities after rash eradication, with lifelong immunity development specific to measles22. The fast clearance period is followed by a slow clearance period, and MeV-RNA cannot be detected although it can exist for a long time in lymphatic and other tissues. Past studies on RNA sequences of late-stage measles did not detect mutations in the and genes. The data available explains the long-term existence of MeV-RNA due to its slow clearance without mutation and ability to escape the immune system. The existence of RNA indicates that the low level of replication in tissues facilitates the maturation of the immune response to provide lifelong protection against reinfection. Further studies are needed to better understand the mechanism of MeV-RNA clearance21.

In the present study, the MeV-RNA was detected in the plasma samples but not in the tissues up to day 30 post injection. This may be due to the amount of virus in the plasma being higher than in the tissue. The determination of the existence of MeV in organs at different times in experimental animals is important in clinical practice to determine the dose and the distance between the treatment cycles for patients with cancer. In our research, determining the existence of the virus after 30 days showed that MeV in the organs could no longer be detected. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct research with a larger sample size and determine the existence of MeV at an earlier stage with more timepoints.

Preclinical safety testing of vaccines involves not only the selection of appropriate species but also an assessment of the immunogenic potential of such preparations23. Our results showed that IgG measles antibodies were positive on days 15, 30, and 60 post injection, which is consistent with other studies. Myers. showed that measles IgG antibodies appeared after 15 days16. Rita et al. showed that the positive rates of IgG after 1 week, 2 weeks, 3 weeks and 4 weeks post-injection with Schwartz MeV were 0%, 14%, 81% and 85% respectively24. Another study showed that 87% of monkeys were negative for IgG antibodies in the plasma 11 days post injection with MeV1-F4 and Rouvax vaccine. However, On day 29 after injection, 100% of monkeys vaccinated with Rouvax and MeV1-F4 were found to have IgG antibodies in their plasma, suggesting that measles antibodies may not have been produced until day 11 after injection11. Our results showed that the MeV manufactured by POLYVAC has strong immunity.

MeV can cause organ damage in three ways: infection, viral replication, and immune response producing neurotoxic materials and allergic reactions(25). Therefore, high doses of MeV would probably induce toxicity of multiple organs. However, we observed non-significant histopathological changes in brain, salivary, lungs, heart, liver, kidneys, and spleen in the monkeys exposed to high therapeutic doses, suggesting the safety of the test material. The limitations of the current study are that the number of monkeys was quite small and the time of follow-up was short. Therefore, further research should be conducted with larger sample sizes, other primates, and longer follow-up periods.

Conclusions

There were no significant abnormalities in the physical, clinical, hematological, and biochemical parameters after the intravenous injections of high doses of measles vaccine. The vaccine strain of MeV existed in monkey plasma until day 30, and the measles IgG antibody could be detected after 15 days following injection. The viruses were not detected in the tissues and had no damaging effect on the target organs. Our systematic preclinical safety results indicate the safety of the concentrated measles vaccine for two months of clinical trials with monkeys.

Abbreviations

ALT: Alanine aminotransferase

Acknowledgments

All authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Key scientific program state-level, Ministry of Science and Technology, Vietnam, code: KC10 /16-20 under grant number KC10.27/16-20.

Author’s contributions

DT Chung, HT Long, NT Tung, HA Son and NL Toan designed study. DT Chung, HT Long, HV Tong, NT Hang, NT Huong, BK Cuong, PV Tran, NT Linh, ND Hien, CV Mao, ND Thuan and NL Toan were involved in animal recruitment and sample collection. DT Chung and HT Long were involved in animal recruitment and sample collection, analyzed and interpreted the data. DT Chung, HT Long, HV Tong and NL Toan participated in drafting and writing the article. NT Tung and HA Son were involved in all aspects of the work through correspondence. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Ministry of Science and Technology, Vietnam, code: KC10 /16-20 under grant number KC10.27/16-20.

Availability of data and materials

Data and materials used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasionable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.