CTGF-Primed Wharton’s Jelly Mesenchymal Stem Cells Enhance Collagen Expression for Soft Tissue Regeneration

- Department of Pre-clinical Sciences, M. Kandiah Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, Sungai Long Campus, Selangor, Malaysia

- Department of Human Anatomy, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Binzhou Medical University, Yandai, Shandong, China

- Department of Medicine, M. Kandiah Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, Sungai Long Campus, Selangor, Malaysia

- School of Pharmacy, University of Nottingham Malaysia, Jalan Broga, Semenyih, Selangor, Malaysia

- Faculty of Allied Health Sciences, AIMST University, Bedong, Kedah, Malaysia

Abstract

Background: Connective Tissue Growth Factor (CTGF) is a matricellular protein implicated in modulating mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) behaviour and extracellular matrix remodelling. This study investigated the dose-dependent effects of CTGF, in the presence or absence of Vitamin C, on Wharton’s Jelly-derived MSCs (WJ-MSCs) with respect to morphology, immunophenotype, collagen gene expression, and protein secretion.

Methods: WJ-MSCs were expanded in vitro and treated with CTGF (0–120 ng/mL) and/or 0.5 mM Vitamin C. Morphological changes were evaluated by light microscopy, while flow cytometry was used to analyze surface marker expression (CD73, CD90, and CD105). Collagen gene expression (Col1a1 and Col3a1) was quantified by RT-qPCR, and protein secretion was measured with ELISA.

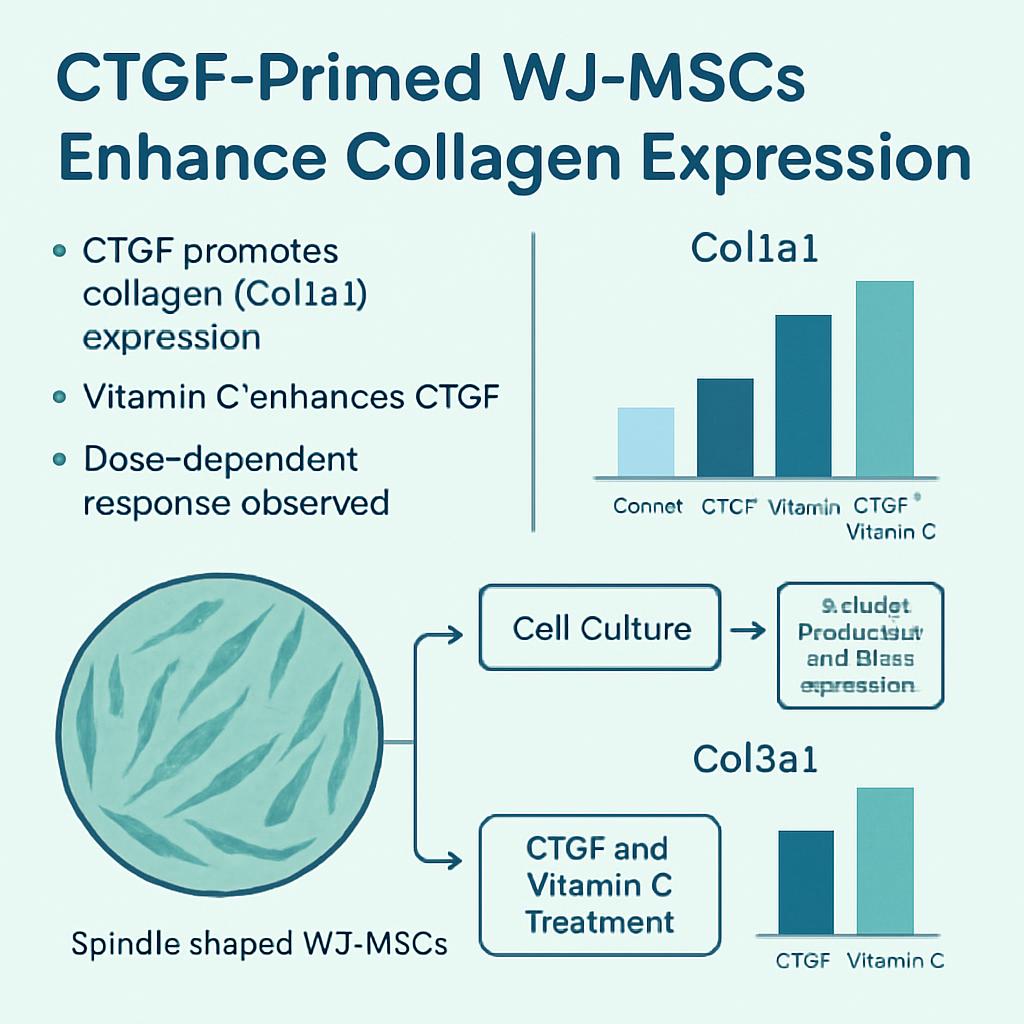

Results: CTGF-treated WJ-MSCs maintained a spindle-shaped morphology and confluent monolayer organization. CD73 expression remained stable at high levels, whereas CD90 and CD105 expression was modulated in a dose-dependent manner. Vitamin C alone downregulated CD105, but this was mitigated by CTGF co-treatment. Col1a1 expression and secretion were significantly increased by CTGF at 50 ng/mL, reaching a maximum at 100 ng/mL with reduced inter-experimental variance. Col3a1 expression was decreased following treatment with CTGF at 10 ng/mL, suggesting a shift in collagen subtype balance. ELISA corroborated increased collagen secretion upon CTGF stimulation.

Conclusion: CTGF, particularly at 100 ng/mL in combination with Vitamin C, promotes mesenchymal marker expression, stimulates Col1a1 synthesis, and supports an immunoprivileged phenotype in WJ-MSCs. These findings underscore the potential of CTGF for regenerative strategies aimed at extracellular matrix remodelling and targeted cell therapy.

Introduction

Soft tissue injuries, which encompass damage to tendons, ligaments, fascia, and muscles, are common clinical presentations that contribute substantially to pain, functional impairment, and healthcare burdens 1,2. These injuries often result from trauma, repetitive strain, or degenerative changes, and their management remains challenging due to their limited intrinsic healing capacity and the risk of fibrosis or incomplete regeneration 3. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) offer a promising avenue for soft tissue repair owing to their multipotent differentiation capacities, immunomodulatory effects, and paracrine signaling 4. However, optimizing MSC behavior in vitro is critical to enhance their therapeutic efficacy 5. Preconditioning strategies using defined bioactive molecules may enhance MSC regenerative performance and ensure consistency in clinical applications. Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), a matricellular protein involved in extracellular matrix remodeling and wound healing, is naturally upregulated during the proliferative phase of soft tissue repair 6. Its role in modulating fibroblast activity and promoting matrix deposition highlights its potential to direct MSCs toward a reparative phenotype 7,8. Culturing MSCs with CTGF may enhance their regenerative profile, augment extracellular matrix synthesis, and better prepare the cells for therapeutic use in soft tissue injury contexts 9. This study investigates the effects of CTGF supplementation on MSCs in vitro, aiming to establish a biologically informed culture strategy that supports their translational application in regenerative medicine.

Methods

Wharton’s Jelly Mesenchymal Stem Cell Expansion, Characterisation, and Storage

Human Wharton’s jelly–derived mesenchymal stem cells (WJ-MSCs) were obtained from Cryocord Laboratories Sdn. Bhd. (Malaysia). Cells were seeded in T-75 flasks and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium–low glucose (DMEM-LG; Gibco) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) and 1 % penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco), yielding a final composition of 89 % DMEM-LG. Cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5 % CO, and the medium was replaced every 2–3 days until the cells reached approximately 80 % confluence.

When cultures reached 80–90 % confluence, cells were sub-cultured at an initial density of 3.75 × 10 cells per T-75 flask and expanded to passage 4. For cryopreservation, cells were resuspended in freezing medium consisting of 80 % DMEM-LG, 10 % FBS and 10 % dimethyl-sulfoxide (DMSO), then stored in liquid nitrogen until further use.

Phenotypic characterisation was performed using the BD Stemflow Human MSC Analysis Kit (BD Biosciences), which detects the positive surface markers CD73, CD90 and CD105. Flow-cytometric analysis confirmed the MSC phenotype based on the positive expression of these markers, in accordance with International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) criteria 10.

CTGF Culture Conditions

On day 4 of culture, when WJ-MSCs had reached approximately 80 % confluence, ascorbic acid (vitamin C, 50 µg mL) was added to all experimental groups except the untreated control. The cells were subsequently allocated to six experimental conditions: (i) untreated control (0 ng mL CTGF, without vitamin C); (ii) vitamin C control (0 ng mL CTGF, with vitamin C); and (iii) CTGF-treated groups receiving 10, 50, 100, or 120 ng mL CTGF in the presence of vitamin C. Cultures were then maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5 % CO for five additional days post-treatment.

Multicolour Immunophenotyping Analysis

On Day 5, cells from all experimental groups were harvested for flow-cytometric analysis. The cells were trypsinized (Gibco), centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 min at room temperature (15–25 °C) with the brake engaged, and washed three times with 1 % bovine serum albumin (BSA) to eliminate residual medium and debris. Following the final wash, the supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellet was resuspended and stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies specific for CD105, CD73, and CD90 (MSC Analysis Kit, BD Biosciences). Samples were subsequently incubated in the dark at room temperature for 20 min before acquisition on a FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Quantitative Real Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from all groups on Day 5 using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RNA purity was evaluated by measuring the A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios with a Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). Only samples possessing A260/A280 values of 1.75–1.84 and A260/A230 values of 2.0–2.2 were advanced to cDNA synthesis.

Quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was conducted on a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using PowerUp SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Primers specific for Col1a1, Col3a1, and the housekeeping gene GAPDH were adopted from previous studies 11,12,13 and are summarised in

Primers Sequence for qRT-PCR

| GADPH | Forward’ | 5’ – GTC TCC TCT GAC TTC AAC AGC G – 3’ |

| Reverse’ | 5’ – ACC ACC CTG TTG CTG TAG CCA A – 3’ | |

| Col1a1 | Forward’ | 5’ – AGG GCC AAG ACG AAG ACA TCC C – 3’ |

| Reverse’ | 5’ – TGT CGC AGA CGC AGA TCC G – 3’ | |

| Col3a1 | Forward’ | 5’ – CGA GGT AAC AGA GGT GAA AGA – 3’ |

| Reverse’ | 5’ – AAC CCA GTA TTC TCC GCT CTT – 3’ |

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Col1a1 and Col3a1 protein concentrations in culture supernatants were quantified using commercially available ELISA kits (Elabscience) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Supernatants were harvested on Day 5, cleared by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 20 min at 2–8 °C, and subsequently analysed. Calibration curves were constructed from serial dilutions of reconstituted standards, and protein concentrations were calculated by interpolating background-corrected optical density (OD) values obtained at 450 nm on a TECAN Infinite F200 microplate reader. Each sample was assayed in triplicate, and mean values were used for statistical analyses. The entire experiment was performed in two independent replicates.

Statistical Analysis

Data from flow cytometry, qRT-PCR, and ELISA were analysed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test in SPSS version 26. All results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation from two independent replicates. Graphs were generated using Microsoft Excel 365. Statistical significance was set at < 0.05.

Results

Cell Morphology and Confluence

By day 4 of culture, passage 1 Wharton’s jelly–derived mesenchymal stem cells (WJ-MSCs) reached 80–90 % confluence and displayed the characteristic spindle-shaped morphology indicative of healthy proliferation and mesenchymal lineage (Figure 1A). Baseline examination revealed no morphological abnormalities. Experimental interventions were initiated at passage 4; connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) was added on day 4. By day 9, after exposure to CTGF and vitamin C, the cells maintained their elongated morphology, although alignment and density varied depending on the treatment condition (Figure 1B–G). The combined administration of 0.5 mM vitamin C with CTGF (50–150 ng/mL) promoted greater morphological uniformity and preserved monolayer integrity. No features suggestive of senescence or cellular degeneration were detected. The immunophenotypic profile of WJ-MSCs provided by Cryocord Laboratories is presented in

Morphological progression and treatment response of Passage 1 WJ-MSCs. Phase-contrast microscopy images showing Wharton’s Jelly-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (WJ-MSCs) under pre-experimental and experimental conditions. Panel A shows spindle-shaped morphology of Passage 1 WJ-MSCs at Day 4 of culture, prior to treatment. Cells exhibit elongated bodies, central nuclei, and cytoplasmic extensions, with uniform alignment and no morphological abnormalities indicative of healthy proliferation. Panels B–G represent experimental conditions assessed at Day 9 of culture. Panel B shows the Non-Vitamin C control, while Panel C shows the Vitamin C control (50 µg/mL). Panels D–G depict CTGF treatment at 10, 50, 100, and 120 ng/mL, respectively, combined with Vitamin C (50 µg/mL). Cells across treatment groups maintained spindle-shaped morphology with varying degrees of alignment and density. No signs of senescence, detachment, or degeneration were observed. Scale bar = 100 µm. Abbreviations: WJ-MSCs, Wharton’s Jelly Mesenchymal Stem Cells; CTGF, Connective Tissue Growth Factor.

Immunophenotype expression of passage 2 Wharton’s Jelly Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (WJ-MSCs)

| Marker-Fluorochrome | Immunophenotype Expression (%) | ISCT Criteria | Impact on MSCs behaviour |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Marker Cocktail: | |||

| CD90-FITC | 98.5% | >95% | Influences MSCs homing and interaction with ECM components |

| CD73-APC | 99.4% | >95% | Enhances immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory effects |

| CD105-PerCP-cy5.5 | 99.2% | >95% | Regulates angiogenesis, ECM remodelling, and immunomodulation |

| Negative Marker Cocktail: | |||

| CD45/CD34/CD11b/CD19/HLA-DR PE | 2.0% | <2% | High expression indicate contamination |

Immunophenotypic Profile of MSCs

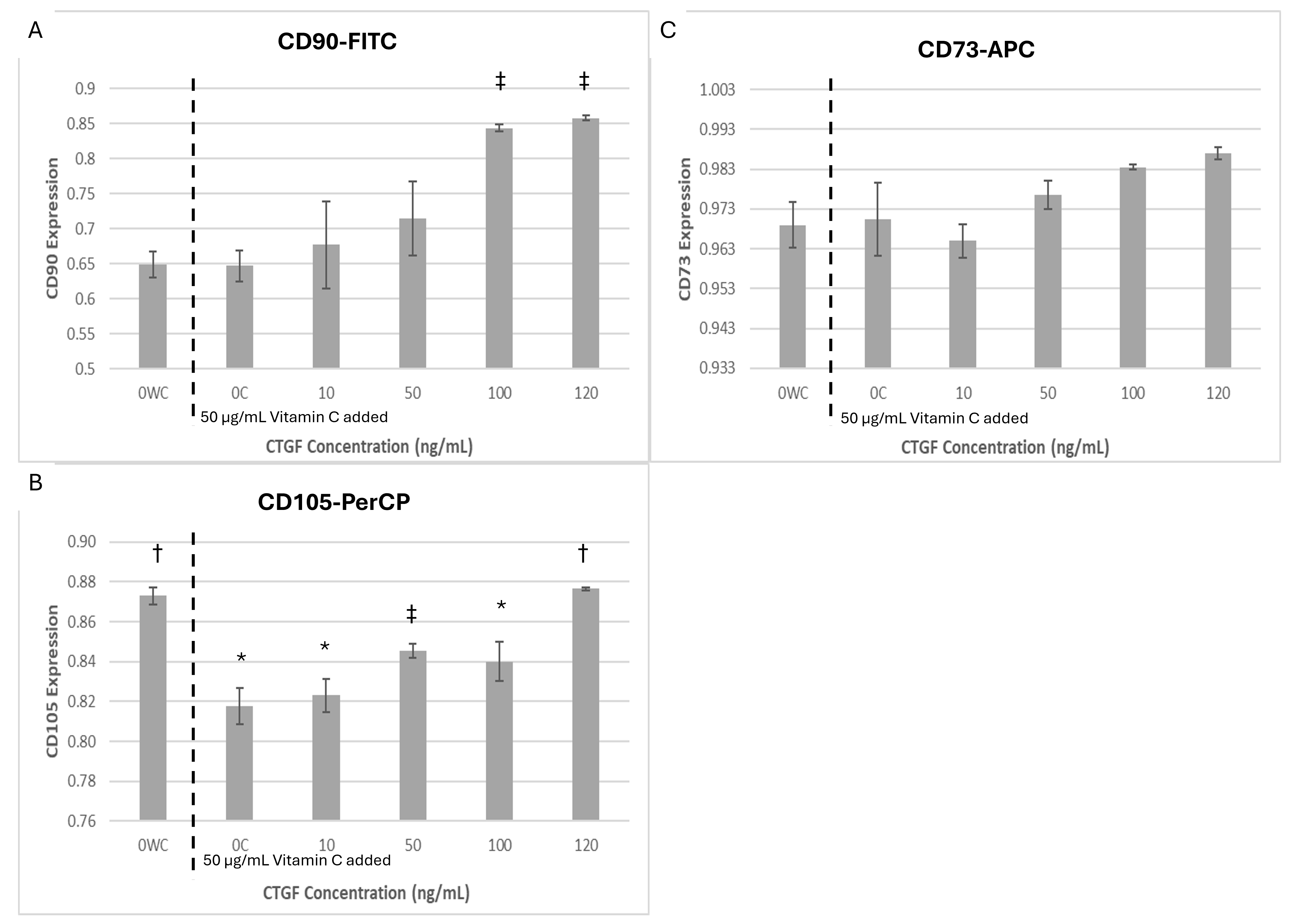

Flow cytometry confirmed robust positive expression of CD73, CD90, and CD105 across all experimental groups (Figure 2). CD73 remained uniformly high (>95 %), indicating maintenance of immunoprivilege. CTGF-treated groups demonstrated increased CD90 and CD105 expression, with the greatest effects observed at 100 and 120 ng/mL. Vitamin C alone decreased CD105 levels, but combined treatment with CTGF restored its expression in a dose-dependent manner (p < 0.05). CD90 was therefore selected for subsequent dose optimisation because of its consistent up-regulation and established immunomodulatory importance.

Expression of mesenchymal surface markers CD90, CD105, and CD73 in WJ-MSCs following CTGF and Vitamin C supplementation. Bar graphs show mean expression levels (± SD) of CD90-FITC (A), CD105-PerCP (B), and CD73-APC (C) in Wharton’s Jelly-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (WJ-MSCs) cultured with 0.5 mM Vitamin C and increasing concentrations of Connective Tissue Growth Factor (CTGF; 0, 50, 100, and 200 ng/mL). CTGF treatment in the presence of Vitamin C induced a progressive increase in CD90 expression, a corresponding decrease in CD105 expression, and relatively stable CD73 expression across all conditions. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Symbols indicate: p < 0.05 vs. untreated control (OWC); † p < 0.05 vs. Vitamin C control (OC); † p < 0.05 vs. both controls.

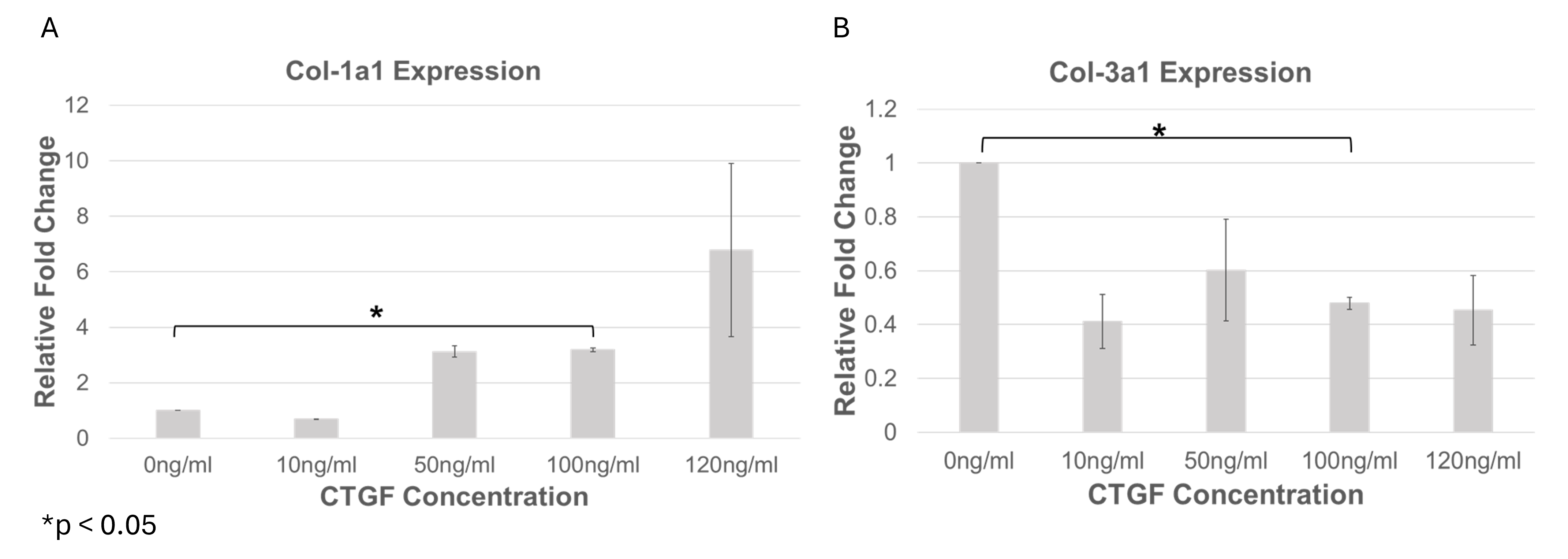

Gene Expression of Collagen Markers

Col1a1 expression was increased in response to CTGF concentrations ≥50 ng/mL, reaching a maximum at 120 ng/mL, although with substantial variability. Conversely, exposure to 100 ng/mL CTGF produced a significantly elevated yet more consistent induction of Col1a1 compared with control (p < 0.05). Col3a1 expression peaked in the vitamin C–treated controls and declined progressively at CTGF concentrations ≥10 ng/mL (Figure 3). Collectively, these data indicate that CTGF skews the collagen expression profile toward Col1a1. A concentration of 100 ng/mL CTGF was therefore chosen for subsequent experiments because it provided an optimal balance between Col1a1 induction and Col3a1 suppression.

CTGF dose-dependent modulation of collagen gene expression in WJ-MSCs. Bar graphs show mean fold change (± SD) in Col1a1 (A) and Col3a1 (B) gene expression in Wharton’s Jelly-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (WJ-MSCs) following supplementation with increasing concentrations of Connective Tissue Growth Factor (CTGF; 0, 50, 100, and 120 ng/mL) in the presence of 0.5 mM Vitamin C. Col1a1 expression increased in a dose-dependent manner, with the highest expression observed at 120 ng/mL CTGF, though this condition exhibited high variability. In contrast, 100 ng/mL CTGF yielded significantly elevated Col1a1 expression with lower standard deviation (p < 0.05 vs. control), indicating a more consistent transcriptional response. Col3a1 expression was highest in untreated and Vitamin C control groups and progressively decreased with CTGF concentrations ≥10 ng/mL. This inverse relationship suggests a shift in collagen subtype balance favoring Col1a1 over Col3a1 under CTGF stimulation.

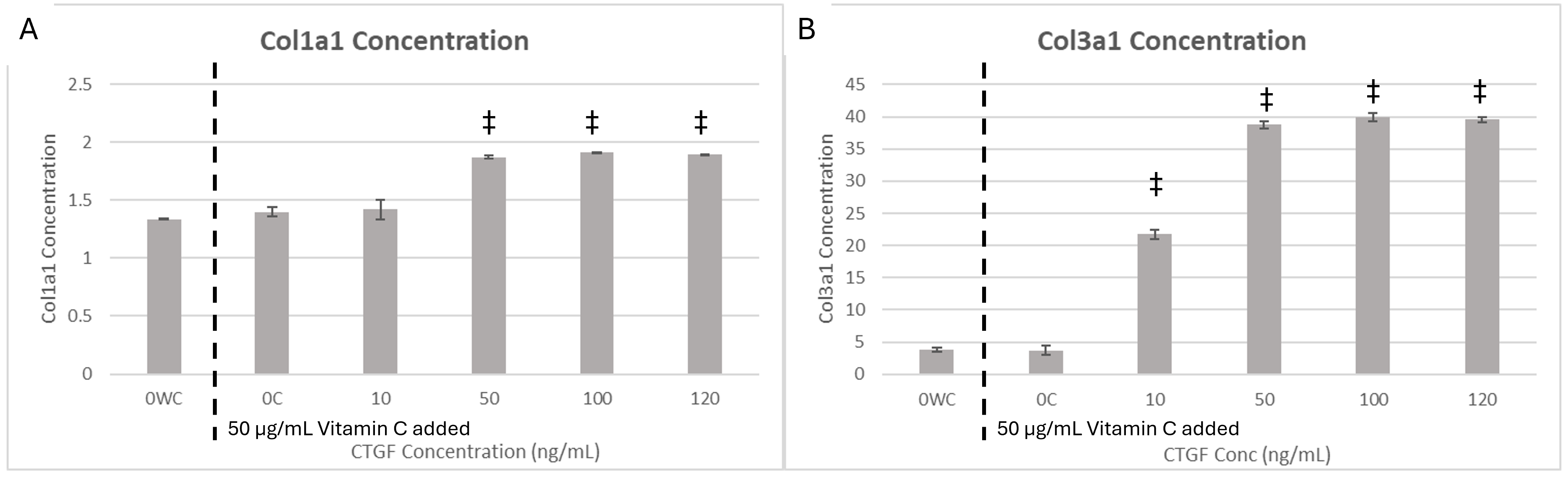

Protein Quantification via ELISA

ELISA analysis demonstrated a significant elevation of Col1a1 secretion in WJ-MSCs exposed to CTGF concentrations of ≥50 ng/mL (p < 0.05); however, no further increase was observed between 50, 100 or 120 ng/mL, suggesting that the response reached a plateau (Figure 4A). In contrast, Col3a1 secretion began to rise at ≥10 ng/mL CTGF and attained its maximum between 50 and 120 ng/mL (Figure 4B). Collectively, these findings substantiate the contribution of CTGF to collagen biosynthesis and underscore its potential utility in regenerative matrix remodelling.

CTGF-induced collagen secretion in WJ-MSCs quantified by ELISA. Bar graphs show mean protein concentration (± SD) of Col1a1 (A) and Col3a1 (B) secreted by Wharton’s Jelly-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (WJ-MSCs) cultured with 50 µg/mL Vitamin C and increasing concentrations of Connective Tissue Growth Factor (CTGF; 0, 10, 30, 50, and 120 ng/mL). Col1a1 secretion was significantly elevated in CTGF-treated groups at concentrations ≥50 ng/mL (p < 0.05 vs. control), with no significant differences between the 50, 100, and 120 ng/mL conditions, indicating a plateau beyond the 50 ng/mL threshold. Col3a1 secretion increased with CTGF concentrations ≥10 ng/mL, peaking between 50 and 120 ng/mL. This dose-responsive pattern suggests that CTGF promotes synthesis of both Col1a1 and Col3a1, though with distinct activation thresholds. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Symbols indicate: *p < 0.05 vs. untreated control (OWC); † p < 0.05 vs. Vitamin C control (OC); ‡ p < 0.05 vs. both controls.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that CTGF, particularly when combined with vitamin C, modulates key phenotypic and extracellular matrix properties of WJ-MSCs in a dose-dependent manner. Morphological analysis showed that treated cells retained their spindle-shaped morphology and monolayer integrity, with increased alignment and density under combined CTGF/vitamin C exposure. These observations indicate that CTGF does not impair mesenchymal morphology and may enhance cytoskeletal organisation and cell–cell cohesion 15,16,17. To isolate the biochemical contribution of vitamin C to collagen synthesis, two control groups were included: one supplemented with vitamin C (50 μg/mL) and one without. Vitamin C serves as a cofactor for prolyl and lysyl hydroxylases, which hydroxylate pro-collagen chains, thereby promoting the formation of stable triple-helical collagen for extracellular secretion 18. This design enabled discrimination between the baseline effects of CTGF and those attributable to vitamin C.

Immunophenotypic analysis revealed a stable level of CD73 expression across all conditions, reinforcing the immune-privileged status of WJ-MSCs 19. Although vitamin C alone downregulated CD105, co-treatment with connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) restored its expression, indicating a regulatory interplay between differentiation cues and matrix signaling. CD90 expression was consistently upregulated following CTGF exposure, supporting its role in immunomodulation and tissue repair 20,21. On the basis of these observations, 100 ng·mL CTGF was selected as the optimal dose for downstream applications, owing to its balanced enhancement of CD90 and CD105 without compromising CD73. This concentration reliably promoted immunomodulatory and regenerative marker expression while maintaining a mesenchymal identity, suggesting a favourable phenotypic profile for therapeutic use.

Although CD105 expression continued to rise at 120 ng/mL, CD90 reached a plateau, and CD73 remained stable, indicating that higher concentrations may not provide additional benefits for enhancing immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory properties 22. Notably, CD90 plays a pivotal role in mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC) homing and interaction with extracellular-matrix (ECM) components, thereby facilitating adhesion, migration, and tissue integration 23. These processes are essential for MSC survival, differentiation, and therapeutic efficacy within the lesion microenvironment. While CD105 contributes to angiogenesis, ECM remodelling, and TGF-β-mediated immunomodulation, its involvement in direct MSC homing and tissue anchorage is less pronounced than that of CD90 24,25. Accordingly, a concentration of 100 ng/mL—which maximally up-regulates CD90 and restores CD105 without altering CD73—appears to represent a biologically responsive threshold that optimizes beneficial signalling while preserving phenotypic stability and functional competence.

At the transcriptional level, CTGF elicited a dose-dependent upregulation of Col1a1, with 100 ng/mL producing the most consistent increase. Col3a1 expression declined at CTGF concentrations ≥ 10 ng/mL, suggesting a shift toward a fibrotic matrix phenotype 26. These gene-level findings were corroborated by ELISA, which confirmed elevated secretion of both Col1a1 and Col3a1 proteins, although Col1a1 reached a plateau at concentrations exceeding 50 ng/mL. This differential regulation of collagen isoforms underscores CTGF’s role in matrix remodeling and supports its application in regenerative strategies targeting fibrotic or scaffold-based environments 27.

Importantly, collagen type I represents the predominant structural collagen in the skin, tendons, bone, and other connective tissues, and is essential for mechanical strength and long-term tissue integrity. During the maturation phase of wound healing, it replaces collagen type III, forming organised, highly cross-linked fibrils that resist tensile stress 28. Conversely, collagen type III predominates during the early stages of repair, where it supports angiogenesis and provisional matrix formation, yet is gradually downregulated as the tissue matures 26. Therefore, CTGF-induced upregulation of Col1a1, together with concurrent downregulation of Col3a1, reflects the transition from early repair to matrix consolidation, aligning with therapeutic objectives in scaffold-based regeneration and in fibrotic tissue stabilisation. Collectively, these findings underscore CTGF’s capacity to reinforce mesenchymal identity, modulate collagen synthesis, and preserve immunoprivilege in WJ-MSCs. The interplay between CTGF and vitamin C offers a tunable platform for optimising stem-cell behaviour in therapeutic contexts.

Limitation and Future Directions

This study provides valuable insights into the dose-dependent effects of CTGF on Wharton’s Jelly–derived mesenchymal stromal cells (WJ-MSCs), particularly with respect to immunophenotypic modulation and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling. Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, functional assays, including collagen-gel contraction, migration (scratch or wound-healing), and scaffold-adhesion tests, were not performed because of resource constraints. Such assays are critical for confirming ECM remodeling capacity, migratory behavior, and scaffold-integration potential in CTGF-treated MSCs and will therefore be prioritized in future studies.

Second, although biological replicates were included, the overall sample size was modest, and the lack of functional and in vivo validation constrains both the generalizability and translational relevance of the present findings. This choice was intentional to comply with the 3Rs ethical framework, specifically the principles of Reduction and Replacement, by minimizing animal use during the preliminary optimization phase. We nevertheless recognize that in vivo experiments will be indispensable to verify the therapeutic efficacy and safety of the optimized CTGF dose in a physiological setting.

Consequently, potential applications—such as enhanced scaffold integration or improved regenerative outcomes—should be regarded as promising directions rather than definitive conclusions. Future work will therefore focus on corroborating these findings through functional assays and appropriate animal models, thereby facilitating the clinical translation of CTGF-based interventions.

Conclusion

Supplementation with CTGF—particularly at 100 ng/mL in conjunction with vitamin C—augments mesenchymal marker expression, increases Col1a1 synthesis, and preserves CD73-mediated immunoprivilege in WJ-MSCs. These observations highlight CTGF's utility as a matrix-modulating molecule for regenerative medicine, with putative applications in scaffold integration, wound repair, and site-specific cell therapy. Nevertheless, because the current dataset is preliminary and lacks functional confirmation, these applications remain hypothetical. Subsequent investigations should characterize long-term functional outcomes, extracellular-matrix deposition kinetics, and in-vivo biocompatibility to corroborate the clinical translatability of CTGF-based strategies.

Abbreviations

ANOVA: Analysis of Variance; BSA: Bovine Serum Albumin; CD105: Cluster of Differentiation 105; CD73: Cluster of Differentiation 73; CD90: Cluster of Differentiation 90; Col1a1: Collagen Type I Alpha 1 Chain; Col3a1: Collagen Type III Alpha 1 Chain; CTGF: Connective Tissue Growth Factor; DMEM-LG: Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium-Low Glucose; DMSO: Dimethyl Sulfoxide; ECM: Extracellular Matrix; ELISA: Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay; FBS: Fetal Bovine Serum; GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde 3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase; HSD: Honestly Significant Difference; ISCT: International Society for Cellular Therapy; MSC: Mesenchymal Stem Cell; qRT-PCR: Quantitative Real Time Polymerase Chain Reaction; RT-qPCR: Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction; TGF-β: Transforming Growth Factor Beta; WJ-MSCs: Wharton's Jelly Mesenchymal Stem Cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Cryocord Laboratories Sdn Bhd (Malaysia) for sponsoring the WJ‑MSCs used in this study. This work was supported by the UTAR Research Fund under Grant Nos. IPSR/RMC/UTARRF/2019‑C2/G01 and IPSR/RMC/UTARRF/2021‑C2/G01. We also thank our co‑researchers for their valuable contributions. Finally, we appreciate the constructive feedback from anonymous reviewers, which helped improve the clarity of this manuscript.

Author’s contributions

Quan Fu Gan was involved in conceptualisation, methodology development, data collection, writing the original draft, and funding acquisition. Li Zhang contributed to methodology development and data collection. Soon Keng Cheong participated in conceptualisation, project supervision, and funding acquisition. Kenny Voon and Zhen Yun Siew were responsible for data collection. Chye Wah Yu performed the formal analysis. Pooi Pooi Leong contributed to conceptualisation, methodology development, project supervision, writing (review and editing), and funding acquisition. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the UTAR Research Fund under Grant No. IPSR/RMC/UTARRF/2019-C2/G01 and IPSR/RMC/UTARRF/2021-C2/G01.

Availability of data and materials

Data and materials used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The WJ‑MSCs used in this study were sponsored by Cryocord Laboratories Sdn Bhd (Malaysia), with donor consent obtained by the provider in compliance with institutional and national ethical guidelines.

Consent for publication

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript and consent to its publication. The WJ‑MSCs used in this study were sponsored by Cryocord Laboratories Sdn Bhd (Malaysia), which provided consent for their use and publication in accordance with institutional and national guidelines.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The authors declare that generative AI-assisted technologies (Microsoft Copilot) were used to improve language clarity and formatting during manuscript preparation. No AI tools were used for data analysis, interpretation, or scientific conclusions. The authors take full responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the content.

Competing interests

The authors declare that Cryocord Laboratories Sdn Bhd (Malaysia) sponsored the WJ‑MSCs used in this study. This work was also supported by the UTAR Research Fund. The sponsors had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or manuscript preparation. The authors declare no other competing interests.