Stem cell–derived exosomes in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity: A systematic review of in vivo and in vitro studies

- Isfahan Cardiovascular Research Center, Cardiovascular Research Institute, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

- Student Research Committee, Kashan University of Medical Science, Kashan, Iran

- School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Science, Isfahan, Iran

- Department of Cellular and Molecular Biology and Microbiology, Faculty of Sciences and Biotechnologies, University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran

Abstract

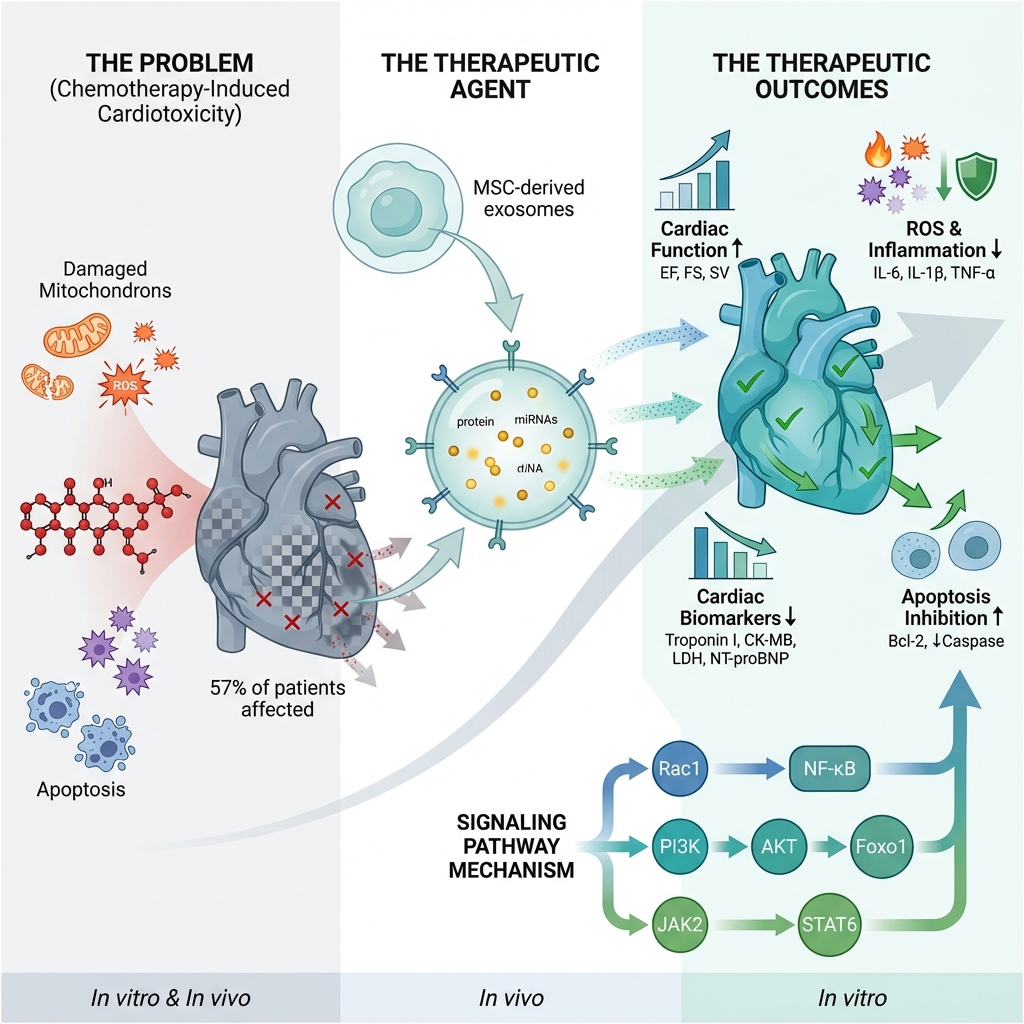

Introduction: Chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity (CIC) is a significant challenge in cancer treatment, with limited therapeutic options available for preventing cardiac damage. This systematic review aimed to summarize the therapeutic efficacy of stem cell–derived exosomes in CIC.

Methods: PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, and Web of Science databases were systematically searched up to April 2024, to identify relevant in vivo and in vitro studies. Two reviewers independently screened and extracted data using a pilot-tested form. The quality of the included studies was evaluated using the SYRCLE risk of bias tool for animal studies and the QUIN (QUality IN vitro) Assessment Tool. Due to heterogeneity in models, exosome sources, isolation methods, dosing, routes, timing, and outcomes, we conducted a narrative synthesis without meta-analysis.

Results: Among the 107 citations obtained from the databases, 27 were included. Exosome treatment improved cardiac function parameters, including left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), fractional shortening (FS), and stroke volume (SV). Exosomes were associated with favorable changes in cardiac biomarker levels, including significant reductions in troponin, creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). Exosomes also reduced inflammation and oxidative stress markers, and ameliorated histopathological changes in cardiac tissues. They were associated with a reduction in apoptotic markers and enhanced cell survival. In addition, exosomes improved angiogenesis in daunorubicin-induced cardiac models. The available evidence suggests the beneficial effects of stem cell–derived exosomes for CIC treatment and prevention.

Conclusions: Stem cell–derived exosomes demonstrate promising therapeutic effects in mitigating chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity by enhancing cardiac function, reducing inflammation and oxidative stress, and limiting apoptosis. These findings support the potential clinical application of exosomes as a novel, cell-free strategy for cardioprotection in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Further clinical trials are warranted to confirm their efficacy and safety.

Introduction

In recent years, novel anti-cancer medications have remarkably improved survival rates of patients with malignancies. However, alongside these benefits, there has been a notable increase in morbidity and mortality among cancer patients due to adverse effects 1. The most significant chemotherapy-induced adverse effect is cardiotoxicity, which can lead to impaired cardiac function, increased morbidity and mortality, and reduced quality of life 1,2. Cardiotoxicity from anti-cancer drugs may cause serious complications, including myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, and hypertrophy. These complications can limit the future use of such medications 3,4. Accordingly, anthracyclines, a primary class of chemotherapeutic agents, have been associated with an increased prevalence of chemotherapy-induced cardiac dysfunction of up to 57% in Western countries 5. Cardiac dysfunction may manifest years after chemotherapy, ranging from asymptomatic changes and subclinical disease to heart failure or death 1,6,7.

Given the widespread use of chemotherapy medications, particularly anthracyclines, numerous pharmacological agents have been investigated for their protective effects against chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity (CIC) 8. Similarly, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been proposed as a means to attenuate cardiotoxicity due to their key functions, including self-renewal and multilineage differentiation potential, pluripotency, and the ability to develop into different cell types 9.

Recent studies have shown that the therapeutic effects of MSCs are attributed to extracellular vesicles (EVs) derived from these cells 10,11. Exosomes are small EVs (30–100 nm) released by various cell types. They carry proteins, lipids, growth factors, and miRNAs, enabling cell-to-cell communication 12,13. They engage target cells via various mechanisms, including promotion of cell proliferation, suppression of apoptosis, attenuation of oxidative stress in recipient cells, regulation of immune responses, and improvement in oxygen delivery 11. Exosomes may serve as an alternative to MSC-based therapies due to their biocompatibility, low immunogenicity, and reduced risk of embolism. They circumvent many drawbacks of cell-based treatments and hold promise for cardiac repair 14,15.

With increasing cancer patient survival, more attention is needed for chemotherapy side effects, particularly cardiotoxicity, and the discovery of more effective treatment methods to ameliorate the cardiotoxic effects of these medications remains a significant challenge. To the best of our knowledge, no prior systematic review has comprehensively evaluated the therapeutic effects of stem cell–derived exosomes in models of chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity. This review aims to fill that gap by synthesizing preclinical evidence from both in vitro and in vivo studies. Therefore, in this systematic review, we aim to summarize the potential of exosomes in the treatment of CIC.

Methods

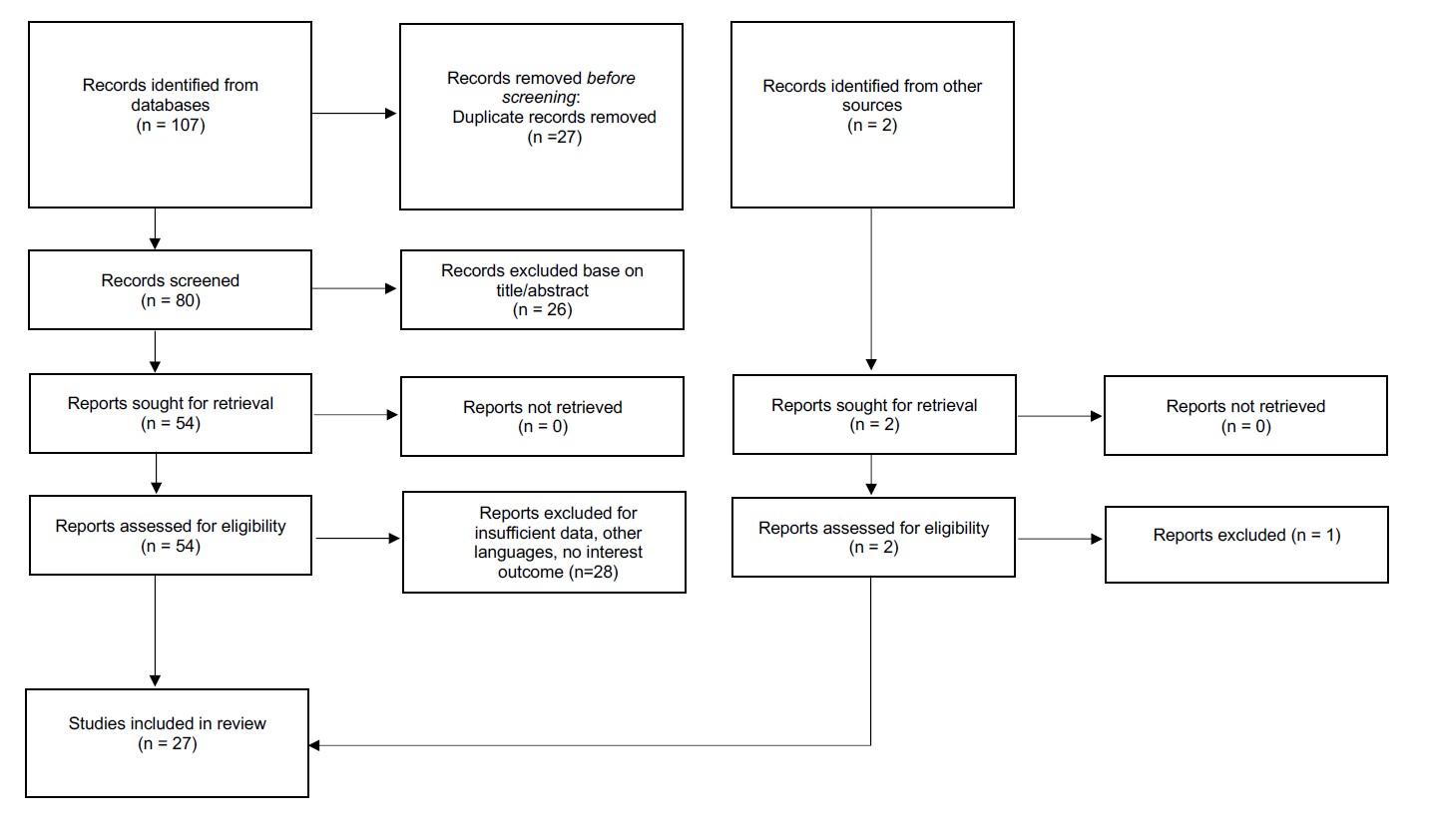

This systematic review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (16; see Table S1). It was not registered.

Search Strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted using three electronic databases from their inception to April 8, 2024, namely PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, and Web of Science. Manual searches for additional studies were also performed using Google and Google Scholar, and the reference lists of included reviews were screened. The search query shown in Table S2 was used for the systematic search. There were no restrictions on study location or publication date.

Eligibility Criteria

Two reviewers (R. A. B. and B. D.) screened the literature according to predetermined inclusion criteria for eligible articles. Inclusion comprised non-duplicate, English-language, in vivo, or in vitro articles evaluating the therapeutic effect of stem cell-derived exosomes on chemotherapy drug–induced cardiotoxicity. We excluded non-English articles, duplicate reports, irrelevant studies, and those reporting only prophylactic effects without investigating therapeutic effects.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Two reviewers (H. S. and Z. G.) independently screened titles and abstracts for duplication and selected potentially relevant articles. All full-text articles were independently reviewed to determine inclusion. EndNote software version 21 was used to remove duplicates from screened records. When data were missing, additional information was requested from the authors.

The following data were extracted from eligible articles using a predesigned Microsoft Excel form: general study parameters (first author, year of publication, and study design), animal model (animal species, animal model, animal sex, and age), experimental sample characteristics, stem cell type and source (isolation method for exosomes, dosage, route, and timing of exosome administration, and particle size), targeted non-coding RNA, and outcomes of interest. Any disagreements in the screening process or data extraction were resolved by discussion and consultation with a third reviewer (M. R. R.).

Outcomes of Interest

All outcomes were continuous; we extracted study-level group means (±SD/SEM) and mean differences (or change-from-baseline, when reported): 1 Cardiac function: LVEF/LVFS, stroke volume; 2 Biomarkers: troponin, CK-MB, LDH, NT-proBNP; 3 Inflammation, oxidative stress: cytokines, ROS, MDA, antioxidant enzymes; 4 Histology, fibrosis: injury, fibrosis scores or % fibrotic area; 5 Cell death: TUNEL %, caspase activity, Bax/Bcl-2; 6 Angiogenesis: capillary density, marker expression; 7 Mitochondrial function: ATP, fusion/fission, biogenesis proteins. Because measures, units, and time points varied across studies, we did not pool effects; results are presented as study-level contrasts and direction-of-effect summaries.

Quality Assessment of Included Studies

Two reviewers (R. A. B. and B. D.) independently assessed the risk of bias and quality of included studies using the SYRCLE risk of bias tool 17. It assesses the risk of bias in ten domains, including selection bias (sequence generation, baseline characteristics, and allocation concealment), performance bias (random blinding and housing, and blinding), detection bias (random outcome assessment and blinding), other biases 17. Responses to these domains were “yes” (low risk of bias), “no” (high risk), or “?” (unclear). For in vitro studies, risk of bias was evaluated with the QUIN (Quality Assessment Checklist) tool, which includes 12 criteria scored as adequate (2 points), inadequate (1 point), or not specified (0 points; not applicable criteria excluded). Studies were classified as having low risk of bias (>70%), medium risk (50%–70%), or high risk (<50%) 18.

Synthesis Methods

Narrative synthesis was performed due to heterogeneity in models, agents, and exosome preparations. Studies were grouped by prespecified outcome domains (function, biomarkers, inflammation, oxidative stress, histopathology, fibrosis, cell death, angiogenesis, mitochondrial function), tabulated with model, intervention details, and summarized by direction of effect. We extracted all measures and time points but prioritized canonical indicators and the latest post-intervention readouts for each summary. Risk of bias (SYRCLE/QUIN) informed interpretation; no meta-analysis or formal assessments of reporting bias or certainty were performed.

Results

Search results

Database searches yielded 107 articles. After removing duplicates, 80 citations were screened, and 54 underwent full-text review. Of these, 27 published papers were deemed relevant and included 19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45. A PRISMA flowchart of the study selection process is presented in Figure 1.

The flowchart of study selection

Study characteristics

The included studies comprised 14 performed in both in vitro and in vivo settings, 8 performed solely in vivo, and 5 performed solely in vitro. Among them, 15 focused on male subjects, whereas 3 examined female subjects exclusively, and 1 included both male and female subjects. Publication years ranged from 2015 to 2024.

For animal species, 13 studies used mice, including 8 using C57BL/6 mice, 2 using CI-1 mice, and 1 using nude mice. Additionally, 7 studies used rats, with 4 using Wistar rats, and 3 using Sprague-Dawley rats. Notably, one study used fertilized chicken eggs for chorioallantoic membrane assays. Among the studies with in vitro components, samples included various cell types, such as rat embryonic cardiomyocyte cells (H9c2), neonatal rat cardiac myocytes (NRCMs), neonatal mouse cardiac myocytes, primary mouse cardiomyocytes, human AC16 cells, human cardiac microvascular endothelial cells, NR8383 rat macrophage cells, patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cell–derived cardiomyocytes (iCMs), and human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hUC-MSCs) from full-term cesarean deliveries; plus mouse ventricular myocytes from C57BL/6 mice, and human induced pluripotent stem cell–derived cardiomyocytes. The characteristics of the included studies are presented in

Summary of characteristic for included studies

| First author | Year | Study Design | Gender | Animal species | Animal model | Age (weeks) | Experimental sample | Stem cell type and source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhang et al. | 2024 | in vivo and in vitro | - | Fertilized eggs of chicken | Chicken Chorioallantoic Membrane | NR | Human cardiac microvascular endothelial cell | MSCs xenogenic in vivo/allogenic in vitro |

| Imam et al. | 2024 | in vivo | M | Rat | Wistar | NR | - | Bone marrow-derived MSCs from Fora and tibiae of Wistar albino rats/allogenic |

| Ali et al. | 2024 | in vitro | - | - | - | - | Rat embryonic cardiomyocyte cells (H9c2) | C57BL/6 mouse bone MSCs xenogeneic |

| Zeng et al. | 2023 | in vitro | - | - | - | - | Embryonic cardiomyocyte cells (H9c2) | Rat Bone marrow stromal cells -allogenic |

| Xiong et al. | 2023 | In vivo | M | Rat | Specific pathogen-free Sprague Dawley | 6 | - | Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell-xenogenic |

| Wang et al. | 2023 | in vivo | M | Rat | Wistar | NR | - | Fourth-geneRation adipose-derived mesenchymal stem from C57 mice xenogenic |

| Duan et al. | 2023 | in vivo and in vitro | M | Mice | C57BL/6 | 8 | H9c2 cardiac myoblast cells | Human trophoblast stem cells xenogenic |

| Desgres et al. | 2023 | in vivo | M | Mice | BALB/c | 9 -12 | - | Cardiac progenitor cells differentiated from human induced pluripotent stem cells - xenogenic |

| Desgres et al. | 2023 | in vivo | F | Rat | Wistar | 8 | - | Human iPSC-derived CPC-xenogenic |

| Yu et al. | 2022 | in vivo and in vitro | M | Mice | Wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 | 8 | Neonatal Rat cardiac myocytes (NRCMs): Normoxic and Hypoxic MSCs | Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells from healthy adults-xenogenic |

| Tian et al. | 2022 | in vivo and in vitro | M | Mice | C57BL/6 | 10 | Neonatal cardiomyocytes of Kunming mice at 1‒3 days postnatally | Bone marrow MSCs |

| Huang et al. | 2022 | in vivo and in vitro | M | Mice | CD1 | 4-6 | Primary mouse cardiomyocytes | human placenta-derived MSCs xenogenic |

| Fan et al. | 2022 | in vivo | NR | nude Mice | NR | NR | - | Bone marrow MSCs from Fur and tibia of three‐week‐old Rats- xenogenic |

| Ebrahim et al. | 2022 | in vivo | M | Rat | Wistar | 8 | - | Rat-adipose-derived MSCs allogenic |

| Zhong et al. | 2021 | in vitro | - | - | - | - | Human AC16 | human umbilical cord MSCs allogenic |

| O'Brien et al. | 2021 | in vitro | - | - | -- | Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cell–derived cardiomyocytes (iCMs) | bone marrow derived MSCs from a young, healthy female-allogeneic | |

| Li et al. | 2021 | In vitro | - | - | - | - | Human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hUC-MSCs) from full-term cesarean section deliveries | human placental MSCs from full-term cesarean section deliveries-allogenic |

| Lei et al. | 2021 | in vivo and in vitro | F | Rat | Sprague Dawley | NR | H9c2 | The third generation of bone marrow MSCs from femur and tibia of female adult Sprague Dawley rats-allogenic |

| Lee et al. | 2021 | in vivo and in vitro | M | Mice | C57BL/6 | 6 | Rat neonatal H9c2 cardiac myoblast cell line | murine embryonic MSCs- allogenic in vivo- xenogenic in vitro |

| Zhuang et al. | 2020 | in vivo and in vitro | M | Mice | C57/Bl6 | 8 | Mouse ventricular myocytes from C57BL/6 mice | Bone marrow-derived MSCs from the femur and tibia of mice pretreated with macrophage migration inhibitory factor-allogenic |

| Xia et al. | 2020 | in vitro | - | - | - | - | Human-induced pluripotent stem cell–derived cardiomyocytes |

Human adipose–derived MSCs some exosomes pretreated with hypoxia-allogenic |

| Ni et al. | 2020 | in vivo and in vitro | M | Mice | C57/Bl6 | 8 | Primary cardiomyocytes from neonatal mice (post 1–2 days) | Human trophoblast stem cells (HTR8-Svneo/ TSCs)-xenogenic |

| Ni et al. | 2020 | in vivo and in vitro | M | Mice | C57/Bl6 | 8-10 | The human cardiomyocyte cell line AC16 | Human trophoblast stem cells (HTR8-Svneo/ TSCs)-xenogenic in vivo, allogenic in vitro |

| Milano et al. | 2020 | in vivo and in vitro | F | Rat | Sprague Dawley | NR | Primary cardiomyocytes from Winstar neonatal rat at p1–3 | Human cardiac-resident mesenchymal progenitor cells from right cardiac atrial appendage tissue specimens obtained from 21 patients |

| Singla et al. | 2019 | in vivo | M/F | Mice | C57BL/6J JAX: 000664 | 10 | Embryonic stem cells from CGR8 -allogenic | |

| Dargani et al. | 2019 | in vitro | - | - | - | - | H9c2 cardiomyoblast |

Mouse embryonic stem cell line, Mouse embryonic fibroblasts cell line-xenogenic |

| Sun et al. | 2018 | in vivo and in vitro | M | Mice | C57BL/6j | 8-10 | Cardiac myocytes from 1-3-day-old C57BL/6j mice | MSCs from the conditioned media of murine-allogenic |

| Vandergriff et al. | 2015 | in vivo and in vitro | M | Mice | CD-1 | 6-8 | Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (NRCMs) | Human cardiac stem cells-xenogeneic |

Risk of bias and quality of the studies

Quality assessment results are presented in Tables S3–S4. Among the 20 in vivo studies, 9 (45%) reported random allocation sequence generation, and 11 (55%) lacked clear reporting on random sequence generation. All studies accounted for baseline differences in participant characteristics. Performance blinding was reported in 4 studies (20%), was unclear in 11 (55%) due to insufficient reporting, and was absent in 5 (25%). Random animal housing was reported in 5 studies (25%); the remainder lacked sufficient information on this. Random outcome assessment was reported in 5 (25%) studies; 15 (75%) lacked sufficient data on random outcome assessment. Detection blinding was reported in 3 studies (15%). Risks of other sources of bias and reporting bias were low across all studies. Additionally, 19 studies showed low risk of attrition bias. For in vitro studies, the QUIN tool was used. All 19 in vitro studies clearly stated their aims and objectives and provided detailed descriptions of methods. Moreover, all adequately described methods for outcome measurement, statistical analysis, and data presentation. However, none reported sample size calculations, interventions, randomization, or outcome assessor blinding. Reporting of control group details and sampling techniques was inadequate in 5 (25%) and 2 (10%) studies, respectively.

Exosome Administration

Exosomes were isolated from various cell types, including bone marrow and umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) from rats, mice, and humans; fourth-generation adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells from C57 mice (ADSCs); human trophoblast stem cells (TSCs); human iPSC-derived cardiac progenitor cells (EV-CPCs); serum extracellular vesicles (EVs) derived from saline-treated rats (SAL-EVs); and serum EVs derived from doxorubicin-treated rats 1 month after saline or doxorubicin treatment; allogeneic embryonic stem cells from the CGR8 mouse ES cell line (ESCs); allogeneic mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs); and human cardiac stem cells (hCSCs). Most studies employed ultracentrifugation or tangential flow filtration for exosome isolation. Size exclusion chromatography was used in four studies, and exosome extraction reagents were used in seven studies. Particle size was reported in 23 studies and ranged from 30 to 450 nm. Administration was primarily via the intravenous route; however, alternative methods of administration, such as intraperitoneal injection, intramyocardial injection, and intraventricular injection, were also used. The characteristics of the stem cell-derived exosomes and their treatment strategies are shown in

Summary of treatment and stem cell-derived exosome parameters

| First author | Year | Particle nm | Isolation method | Route | Timing | Dosage | Type of drug |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhang et al. | 2024 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 150 μg/egg | Doxorubicin |

| Imam et al. | 2024 | Mean 50 nm | Ultracentrifugation | Intraperitoneal | Single injection | 800 μg protein concentration, suspended in 1 mL PBS | Doxorubicin |

| Ali et al. | 2024 | less than 200 nm | Exoquick-TC exosome precipitation solution and then centrifugation | NR | 24 hours after Dox | 10 μg of MSC-exosome | Doxorubicin |

| Zeng et al. | 2023 | 50 to 200 nm | Ultracentrifugation | NR | NR | NR | Doxorubicin |

| Xiong et al. | 2023 | 80-200 nm | Ultracentrifugation | Intraperitoneal injection | 2 times: 1 week before CYP and 1 week later | 3 × 1010 AdMSCs-Exos (in 0.1 mL PBS) | Cyclophosphamide |

| Wang et al. | 2023 | NR | Exo extraction reagent and centrifugation | Injection via the tail vein | Once every 2 days for two consecutive times | 100 μL of exosomes suspension at a concentration of 0.2 mg/mL | Doxorubicin |

| Duan et al. | 2023 | Mean 113 nm | Ultracentrifugation | Intracardiac injection for in vivo | In vitro: 24 h |

25 μl of PBS containing 50 μg exosomes for in vivo 20 µg of exosomes for in vitro | Doxorubicin |

| Desgres et al. | 2023 | 50 nm to 450 nm | Ultracentrifugation | Intravenous injection | Three times over 2 weeks | A total dose of 30E+9 particles | Doxorubicin |

| Desgres et al. | 2023 | Tangential flow filtration | Intravenous injection | 3 equal injections one every 2 days | NR | A total dose of 100E+9/injection | Doxorubicin |

| Yu et al. | |||||||

| Tian et al. | 2022 | 100–150 nm | Ultracentrifugation | Injection via tail vein | Day 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, and 7 | 200ug/100ul PBS | Doxorubicin |

| Huang et al. | 2022 | 100 nm | Differential ultracentrifugation | Injection via the tail vein | Day 8, 11, and 14 | 50μg | Doxorubicin |

| Fan et al. | 2022 | NR |

MSCs and lung tissue-derived cell type (MRC5)-EVs: ultracentrifugation Peripheral blood-derived Evs: Total Exosome Isolation | Injected via the tail vein | NR | 200 μmol/L | Doxorubicin |

| Ebrahim et al. | 2022 | Mode 108 nm | Exosome extraction kit (exosome extraction reagent and then centrifugation) | Intravenous injection | 4 h before injection | 500 µL of PBS containing 20 µg combination of exosomes | Doxorubicin |

| Zhong et al. | |||||||

| O'Brien et al. | 2022 | 40–120 nm | Ultracentrifugation | Intraperitoneal injection |

Protective group: 1 dose of exosomes 1w before the induction of cardiotoxicity. Curative group: Six weeks after the final injection. | each dose 3 × 1010 exosome, re-suspended in 0.1 mL PBS | Doxorubicin and trastuzumab |

| Li et al. | 2021 | 30-100 nm | Ultracentrifugation | NR | NR | MSC with the dosage of 0 μg/ml, 50 μg/ml, 100 μg/ml, and 200 μg/ml | Doxorubicin |

| Lei et al. | 2021 |

large extracellular vesicles (L-EVs): mean 428 nm (350-800 nm) small extracellular vesicles (S-EVs): mean 92 nm (58-122 nm) |

Centrifugation for EV>200 nm → proprietary size-based filtration platform (Exosome Total Isolation Chip – exosome TIC) | NR | 24 h after injection | NR | Doxorubicin |

| Lee et al. | 2021 | 100-200 nm | Differential centrifugation | NR | NR | NR | Doxorubicin |

| Zhuang et al. | 2021 | 30 to 100 nm/ mean 90nm | Centrifugation | Injection via the tail vein | Days 5 and 11 | 3 × 1010 particles each dose resuspended in 0.1 mL of PBS | Doxorubicin |

| Xia et al. | 2021 | Approximately 135 nm | Ultrafiltration | Intravenous injection | At 1 day before injection (15 mg/kg, i.p.), and then every other day for 14 days | in vivo: 4 × 1010 in vitro: MSC at a concentration of 3 × 109 | Doxorubicin |

| Ni et al. | 2020 | 50–100 nm | Exosome quick extraction solution | Intraperitoneal injection | alternative days between treatments (Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday) | 400 µL/injection with 50 µg concentration of exosome | Doxorubicin |

| Ni et al. | 2020 | 50–100 nm | Exosome quick extraction solution | NR | NR | NR | Doxorubicin |

| Milano et al. | 2020 | Mean 101 nm | Differential ultracentrifugation | Intramyocardial injection | One dose | 25 μl of PBS containing 50 μg exosome | Doxorubicin |

| Singla et al. | 2020 | 50–150 nm | Ultracentrifugation | Injected into the left ventricle myocardium | At multiple points | 100 μL per mouse; 1 μg/μL | Doxorubicin |

| Dargani et al. | 2020 | Predominantly <150 nm | Ultracentrifugation | Injection via tail vein | Three doses on Days 5, 11, and 19. | 3 × 1010 particles each dose re-suspended in 0.1 mL PBS | Doxorubicin and trastuzumab |

| Sun et al. | 2019 | NR | Exoquick TC exosome isolation kit and the centrifugation | Intraperitoneal injection | Alternative days of a week between Dox treatments (Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday) | 400 µL/injection with 50 µg concentration of exosome | Doxorubicin |

| Vandergriff et al. | 2019 | NR | Exoquick-TC exosome precipitation solution and then centrifugation | NR | 48h after injection | 10 μg/24h | Doxorubicin |

Cardiac Function

Eighteen studies reported data on cardiac function. Mice treated with exosomes exhibited higher left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), left ventricular fractional shortening (LVFS), and stroke volume (SV) compared to the doxorubicin-induced heart failure group, although these values remained lower than those in the control group 24,27,30,31,36,39,40,41,42,44,45. A study in C57BL/6 mice reported that the exosome-treated group exhibited a higher LVEF and LVFS; however, no significant differences were observed in left ventricular systolic and diastolic diameters 25. In contrast, Ebrahim et al. reported that exosome administration before or after doxorubicin treatment was significantly associated with lower systolic and diastolic left ventricular diameters. Moreover, preventive (pre-treatment) administration of exosomes resulted in better results than post-treatment (curative) administration 31. A cyclophosphamide-based study reported similar findings: exosomes decreased LV diameters and increased LVEF 23. A study by Lee et al. also corroborated a decrease in left ventricular end-systolic diameter/volume (LVESD/V), left ventricular end-diastolic diameter/volume (LVEDD/V), and increases in fractional shortening (FS) and ejection fraction (EF) after exosome administration 36. However, two studies found that exosomes did not significantly affect cardiac function parameters, such as LVEF, LVFS, basal circumferential strain, basal endocardial circumferential strain, basal epicardial circumferential strain, and global longitudinal strain 26,33.

Cardiac biomarkers

Eight studies reported changes in cardiac enzyme levels. A study by Imam et al. 20 on Wistar albino rats reported that exosomes decreased troponin I, creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). Consistent with these results, another study on Sprague-Dawley rats treated with cyclophosphamide reported that combination treatment with exosomes decreased LDH, troponin, and CK-MB levels 23. Another study on Sprague-Dawley rats/H9c2 cells reported that exosomes decreased the levels of troponin, CK-MB, and LDH compared to those in doxorubicin-treated rats 35. Ebrahimi et al. evaluated the effects of exosomes in eight-week-old albino rats , comparing three groups: the protective group (that received one dose of exosomes one week before the induction of cardiotoxicity , plus two doses thereafter following trastuzumab administration), the curative group (that received only two doses of exosomes as treatment after cardiotoxicity induction with trastuzumab), and the doxorubicin+trastuzumab control group. The results indicated that both the protective and curative approaches decreased the levels of troponin, LDH, and CK-MB compared to the doxorubicin+trastuzumab control group. Moreover, rats in the curative group had higher levels of these cardiac enzymes, suggesting greater efficacy from exosome administration before chemotherapy 31. Other studies reported that exosomes decreased HF-related cardiac biomarkers, such as atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), N-terminal pro-BNP (NT-proBNP), β-cardiac myosin heavy chain (β-MHC), and collagen I 39,40. Furthermore, a study comparing exosomes with tetrahedral DNA nanostructure (TDN) alone when added to doxorubicin to a combination of exosome-TDN plus cardiomyopathic peptide reported that the latter approach resulted in lower NT-proBNP and troponin levels 30.

Inflammation and oxidative stress

Seventeen studies have examined the effects of exosomes on inflammation and/or oxidative stress. Seven studies reported a significant decrease in ROS following exosome treatment 22,25,28,32,33,41,44. Imam et al. reported that exosomes reduced IL-6 and MDA, while increasing IL-10, GSH, catalase, and the percentage area of Nrf2-positive staining in immunohistochemical analyses 20. Tian et al. 28, Ni et al. 39, and Dargani et al. 43 reported a significant decrease in IL-6 and IL-1β levels after exosome administration. Lei et al. 35 found that exosomal miR-96 reduced TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β levels by inhibiting the Rac/nuclear factor κB pathway. Sun et al. reported that exosomes decreased the mRNA expression of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α and reduced the number of pro-inflammatory macrophages through the JAK2-STAT6 pathway 44. A significant reduction in CD68+, CD11b+, and CD80+ cells and an increase in CD206+ cells were observed in previous studies 30,41,42,44. Zhong et al. 32 and Yu et al. 27 reported a reduction in MDA levels and an increase in GSH levels following exosome therapy. Ebrahim et al. reported a greater reduction in iNOS and MDA levels in the protective group than in the curative group 31. Moreover, higher SOD activity was observed in exosome-treated groups 20,31,32,35.

Histopathological Changes

Histopathological changes were observed in 12 studies. Exosome treatment ameliorated doxorubicin-induced disturbed cardiac architecture, extensive hyalinization, interstitial edema, multifocal leukocytic cell infiltration, fibroblast invasion, and blood vessel congestion 20,29,30,40,45. Exosomes reduced swelling, necrosis, and disarrangement of cardiomyocytes 24. In comparison to the control, heart tissue from the doxorubicin group exhibited enlarged chambers and thinner ventricular walls, which were ameliorated in the doxorubicin + exosome group 25. Exosomes ameliorated retrogressive changes, congestion, increased myocyte cross-sectional area and collagen accumulation, and resultant fibrosis in cardiac tissues 23. Exosomes reduced Collagen-1 and MMP-9 mRNA levels, as well as perivascular and interstitial collagen deposition 20,31,35.

Groups treated with exosomes exhibited reduced intracytoplasmic vacuolization and preserved normal structure and morphology of the myocardium 31. Lei et al. reported that exosomes attenuated doxorubicin-induced loss of cardiac muscle fibers, myocardial vacuole degeneration, and inflammatory infiltration 35. Histological staining of the heart at week 4 revealed that the exosome treatment group had greater myocardial thickness and smaller cardiac chamber diameter compared to the doxorubicin group 44. Furthermore, exosome treatment was associated with a reduction in myofibril loss and cardiac hypertrophy 42.

Apoptosis

The outcomes regarding cell survival and apoptosis were reported in 16 studies. Overexpression of Bcl-2 and downregulation of Bax following treatment with exosomes were reported in seven 23,24,30,31,36,39,40 and three studies, respectively 24,31,34. In addition, one study showed that exosomes decreased the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio 44. Exosomes also inhibited the activity of caspases, including caspase-1, -3, and -9 20,23,24,30,34,39,40, as well as the number of dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL)-positive apoptotic cells 36,44,45. Imam et al. and Sun et al. reported a reduction in Annexin V staining levels after treatment with exosomes 20,44. Moreover, a reduction in p53 expression has been reported in those studies 20,24. Overall, exosomes significantly inhibit apoptosis and promote cell survival.

Angiogenesis

Zhang et al. evaluated the pro-angiogenic efficacy of exosomes using models of daunorubicin-damaged cardiac microvascular endothelial cells and the chicken chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) model of Chicken Chorioallantoic Membrane blood vessels. Their results suggested that administration of 150 μg/egg of exosomes significantly enhanced angiogenesis in the chicken CAM (an in vivo daunorubicin-damaged model) 19. A summary of the outcomes of the included studies is shown in

Summary of key outcomes

| First author | In vivo outcomes | In vitro outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Zhang et al. | Exosomes by the miR-185-5p-PARP9-STAT1/pSTAT1 pathway, significantly improve angiogenesis. | Exosomes by the miR-185-5p-PARP9-STAT1/pSTAT1 pathway, significantly improve migration, proliferation, and angiogenesis. |

| Imam et al. | Exosomes reduced cardiac tissue levels of Troponin I, CK-MB, and LDH. Besides, reduced the inflammatory biochemical markers, adverse histopathological changes, improved myocardial apoptosis by decrease in both genes' expression, act as an antioxidant, and anti-fibrotic. The exosomes significantly modulated biochemical cardiac tissue levels of oxidative stress markers (GSH, Catalase, GPX, MDA, SOD, Nitric oxide), and restored the number of telocytes in cardiac tissue. | |

| Ali et al. | Exosomes increased cell viability, reduced the HMGB1/TLR4 axis, inflammasome formation (NLRP3), pyroptotic markers (Caspase-1, IL-1β, and IL-18), and pyroptotic. | |

| Zeng et al. |

Exosomes reduced pyroptosis, and mitochondrial damage. Exosomes suppressed GSDMD transcription via the PI3K-AKT-Foxo1 axis and improved improve oxidative stress. | |

| Xiong et al. |

Esxosome reduced CYP-induced enhancement in heart weight and heart/body weight ratio, cardiac injury, oxidative stress levels, autophagy, and apoptosis. | |

| Wang et al. |

The LVEF, LVFS, and SV of rats in the exosome group were higher than those in the control group. Exosomes improved heart, decreased apoptosis, increased ATP levels, and suppressed Bax, caspase-3 and p53 protein expression. | |

| Duan et al. |

Exosomes treatment improved EF and FS. Exosomes group had better cardiac function, lower myocardial fibrosis, lower cardiomyocyte mitochondrial fragmentation). |

Exosomes reduced ROS, and apoptosis. Exosomes reduce enhanced mitochondrial fusion via increased Mfn2 expression. |

| Desgres et al. | Exosomes improved early survival and heart contractility | |

| Desgres et al. | Exosomes significantly protect against chemotherapeutic effects on survival, cardiac function and fibrosis, and reduce ferroptosis-related measures. | Exosomes significantly protect against Dox-induced effect on cell viability and reduced ferroptosis-related measures. |

| Yu et al. | Exosomes improved survival rate and reduced fibrosis and inflammation-related mRNAs. | Exosomes improved cell viability and reduced cellular inflammation and oxidative stress. |

| Tian et al. | Exosomes reduced ER stress-induced apoptosis through miR-181a-5p. | |

| Huang et al. |

Exosomes improved cell viability, reduced inflammatory markers and polarized M0 or M1 macrophages to the M2 phenotype. Exosomes reduced damage to heart tissue. decreased cardiac biomarkers, polarized M0 or M1 macrophages to the M2 phenotype, and improved cardiac function | |

| Fan et al. |

Exosomes reduce the effect of Dox on cardiac function, serum cardiotoxicity indices, cardiac tissue injury, cardiac oxidative stress, DNA Damage, apoptosis, and fibrosis in cardiac tissues It also improved cardiac Ca2+ homeostasis. | |

| Ebrahim et al. |

Exosomes significantly reduced oxidative stress levels at the concentrations of 50 μg/ml, 100 μg/ml, and 200 μg/ml. Exosome treatment significantly inhibited Dox-induced apoptosis oxidative stress, LDH, and decreased levels of SOD and NOX4 and NOX2 expression. | |

| Zhong et al. |

Exosomes improved iCM viability and attenuated apoptosis, improved contractility, oxidative stress, ATP production, and mitochondrial biogenesis. Exosomes were found to be enriched in mitochondria, which were shown to be taken up by iCMs. Inhibiting mitochondrial function with 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium reduce these effects. MSC-treated patient demonstrated improved myocardial function and remodeling. | |

| O'Brien et al. | Exosomes reduced cardiac enzymes, oxidadive stress, fibrosis, inflammatory responses, and protect the cardiac function. |

miR-96, derived from exosomes, can inhibit the Rac1/NF-κB signaling pathway, protecting H9c2 cardiomyocytes from Dox-induced toxicity. It can reduce oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis and enhancing cardiac function. miR-96 overexpression inhibited inflammatory responses induced by Dox-induced myocardial toxicity. |

| Li et al. | Exosomes improved cardiac function and play anti-apoptotic role by upregulating Bcl-2 expression. |

Exosomes restore the survivin expression reduced by DOX via Akt activation. Exosomes activate Akt, which activates Sp1 while suppressing p53 activation, resulting in increased survivin expression in Dox-treated cardiomyocytes. |

| Lei et al. | Exosomes reduced cell apoptosis than Dox by the upregulation of hsa-miR-11401. | |

| Lee et al. |

Exosomes significantly increased expression of ejuvenation-related genes, lower senescence-related genes, and improved cardiac function. Exosomes reduced the percentage of cells in the G0/G1 phase, p27 and p16, and SA-β-gal-positive cells. They also elevated telomere length and activity. | Exosomes group had higher ejuvenation-related genes, lower Senescence-related genes, and lower apoptosis. |

| Zhuang et al. | Exosomes significantly improved rejuvenation in cardiomyocytes. Exosomes specifically transported the lncRNA-MALAT1, which inhibited miR-92a-3p, activating ATG4a and enhancing mitochondrial metabolism while additionally contributing to rejuvenation. | |

| Xia et al. | Exosomes reduced the effect of Dox on cardiac function, fibrosis, apoptosis, and inflammation. | Exosomes group had lower cell apoptosis, C-caspase 3 expression and higher Bcl-2 expression. |

| Ni et al. | exosomes significantly protect cardiac function and reduce inflammation and heart failure markers in Dox-induced dilated cardiomyopathy. | Exosomes downregulated YAP signaling and result in significant reduction in apoptosis and fibrosis and protect against Dox-induced pathological changes. |

| Ni et al. | Exosomes improved cardiac function, oxidative stress, and fibrosis. |

Exosomes suppressed oxidative stress in myocytes (p < 0.05) Exosomes improved cell death and expression of miR-146a-5p target genes. |

| Milano et al. |

Exosomes reduced the effect of Dox increased expression of inflammatory markers, pyroptotic markers, cell signaling proteins, heart function, fibrosis, and histopathological changes. Exosomes decreased pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages, and TNF-α cytokine) and increasde M2 macrophages and anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10. Exosomes improved LVIDd, LVIDs, LVEDV, LVESV, FS, and LVEF. Exosomes treatment decreased both vascular and interstitial fibrosis as well as extracellular pro-fibrotic protein MMP-9 in the Dox-induced cardiomyopathy heart. | |

| Singla et al. |

Exosomes decreased the expression of inflammasome, pyroptosis, and proinflammatory cytokines and increased anti-inflammatory cytokines. Exosomes group had higher anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4, IL-9, and IL-13 and lower proinflammatory cytokines Fas ligand, Fractalkine, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (GCSF), IL-12, leptin, stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF1α), TNF-α, and TNF receptor 1. | |

| Dargani et al. | Exosomes improved cardiac function reduced cardiomyocytes apoptosis, cardiac inflammation cytokines production, circulating macrophages amount, and promoting the conversion of macrophages from pro-inflammatory to anti-inflammatory through JAK2-STAT6 pathway. | Cardiomyocytes apoptosis is reduced by exosomes showed by significant reduction in TUNEL ratio. |

| Sun et al. | Exosomes improved cardiac, decreased apoptosis and fibrosis with no adverse immune reaction. | Exosomes reduced apoptosis and fibrosis. |

Discussion

Currently, there is no specific treatment that offers cardioprotection against CIC. This systematic review evaluated the therapeutic effects of stem cell–derived exosomes in both in vitro and in vivo models of CIC. Our results suggest that exosome transplantation can improve cardiac function, reduce fibrosis, and ameliorate elevated inflammation, cardiac markers, and apoptosis induced by chemotherapy drugs.

However, the exact mechanisms of CIC remain unclear. Previous studies have identified that the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the promotion of several inflammation-dependent pathways represent plausible mechanisms of action for these agents 46,47. ROS generation may disrupt mitochondrial function, leading to apoptosis 48. The results of this review demonstrated that exosomes reduced ROS production, expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), lipid peroxidation, and inflammatory markers such as IL-1β, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-18. Furthermore, exosomes inhibit apoptosis by downregulating caspase-3, caspase-1, and p53; upregulating the Bcl-2 protein; and promoting mitochondrial fusion.

Chemotherapy agents may inhibit matrix metalloprotease-1 (MMP-1) in cancer tissues, which reduces the mobility of tumor cells 49. However, this mechanism of action results in the upregulation of other MMPs 50. The activation of other MMPs can promote collagen deposition in cardiomyocytes and activate transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) signaling, leading to cardiac fibrosis 51,52. This review demonstrates that exosomes possess the therapeutic potential to counteract dysregulated MMPs and the TGF-β pathway, which could prove instrumental in safeguarding cardiac function and preventing the progression of cardiac fibrosis induced by chemotherapeutic agents.

Several signaling pathways mediate the cardioprotective effects of stem cell–derived exosomes, as summarized in our tables. These include Rac1/NF-κB, PI3K-AKT-Foxo1, and JAK2-STAT6. Although these pathways differ in their upstream triggers and downstream targets, they converge on key cellular processes, including inflammation suppression, oxidative stress reduction, and apoptosis inhibition. Rac1/NF-κB signaling, for example, reduces oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis, thereby improving cardiac function. The PI3K-AKT-Foxo1 pathway primarily contributes to oxidative stress reduction. The JAK2-STAT6 pathway promotes polarization of macrophages from pro-inflammatory to anti-inflammatory phenotypes, resulting in decreased cardiac inflammation, fewer circulating macrophages, reduced cytokine production, and improved cardiac function and cardiomyocyte survival.

Cardiac biomarkers may be elevated despite normal cardiac echocardiography findings in the first stage of cardiotoxicity 53,54. Recent studies have shown that cardiac biomarkers are valid predictors of CIC. Cardinale et al. demonstrated that an increase in troponin I levels within 72 hours after high-dose chemotherapy predicts declines in LVEF 55. Rüger et al. reported that NT-proBNP levels measured 6 weeks after chemotherapy initiation were associated with cardiotoxicity in patients with early-stage breast cancer 56. Our study found that administration of stem cell–derived exosomes was associated with a significant decrease in cardiac biomarkers, including troponin, NT-proBNP, CK-MB, and ANP. The significant decrease in these cardiac biomarkers following exosome treatment suggests not only a therapeutic effect but also the potential for preventing the onset of LVEF reduction and subsequent functional decline in cardiotoxicity among patients receiving chemotherapeutic drugs.

Although exosomes have shown significant therapeutic effects in preclinical studies, several challenges must be addressed to enable future clinical application. Challenges include the standardization of isolation and purification methods for exosomes, identification of optimal dosing regimens, elucidation of the mechanisms of action underlying their therapeutic effects, and assessment of long-term safety and efficacy in clinical trials. A few ongoing clinical trials are investigating the role of exosomes in cardiovascular diseases, such as atrial fibrillation (NCT03478410) and aortic dissection (NCT04356300). This comprehensive review of the in vivo and in vitro outcomes of exosomes for the prevention and treatment of CIC highlights the potential therapeutic effects of stem cell-derived exosomes. Well-designed controlled clinical trials are warranted to validate the safety and efficacy of exosome treatment for CIC.

To our knowledge, based on a thorough literature search, this is the first systematic review to specifically examine the cardioprotective mechanisms of stem cell–derived exosomes in the context of chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity. By integrating findings across diverse models and exosome sources, our review provides a foundational framework for future translational and clinical research.

This review has several limitations. Considerable heterogeneity existed in the stem cell source, route (of administration), timing (of administration), sample types, animal model, and exosome dosage among the included studies. These methodological variations likely influenced the results of the included studies. Although the heterogeneity in study design prevented a quantitative synthesis, it also complicated the qualitative interpretation of the results. These differences could influence therapeutic outcomes and limit the generalizability of the findings. For instance, studies using human-derived exosomes or specific purification methods may exhibit stronger anti-inflammatory effects, whereas others may differ in their effects on cardiac function. This variability underscores the need for standardized protocols in future research to enable clearer comparisons and more robust conclusions. Notably,

Moreover, the majority of the studies included in this review used doxorubicin to induce cardiotoxicity; thus, the effects of exosomes on cardiotoxicity induced by other chemotherapeutic agents remain unclear. Finally, the follow-up durations in these preclinical studies were relatively short. Further research is necessary to assess the applicability of these findings to clinical settings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, stem cell–derived exosomes were associated with a trend toward higher LVEF and LVFS, and a reduction in levels of troponin and NT-proBNP, in models of CIC. These exosomes were also associated with reductions in oxidative stress, levels of inflammatory markers, and rates of apoptosis. Larger, randomized controlled trials are warranted to confirm these results. Notably, the current evidence is strongest for anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity, particularly doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity, while the efficacy of exosomes to mitigate cardiotoxicity induced by other chemotherapeutic agents such as trastuzumab and cyclophosphamide remains less established and warrants further investigation.

Abbreviations

Funding

None

Authors' contributions

[M.R.R.]: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—review & editing, [G.G.D.]: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—review & editing, [H.S.]: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—original draft; [B.D.]: Investigation, Validation, Visualization; Writing – original draft; [R.A.B]: Investigation; Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft; [Z.G.]: Investigation, Data curation; [M.I.]: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. All authors had full access to all data in the study, approved the final version of the manuscript, and had a final decision to submit for publication. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was not applicable to this systematic review.

Consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publish

Not applicable

Availability of data and material (data transparency)

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The authors declare that they have not used generative AI (a type of artificial intelligence technology that can produce various types of content including text, imagery, audio and synthetic data.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.